The Age of Chaucer 1340 to 1400: History & Social Background

The socio-political state of 14th-century England deeply impacted the works of Geoffrey Chaucer and his contemporaries. Thus, a historical and social background is indispensable to fully understand the Age of Chaucer. Fourteen-century English literature and society were impacted by three major historical events - The Hundred Years' War, the Peasant’s Revolt, and the Black Death.

Overview

- The Feudal English Society

- Hundred Years’ War

- The Black Death

- The Peasants' Revolt

- Religion in the Age of Chaucer

- Monarchs in the Age of Chaucer

The Feudal English Society

During the Age of Chaucer, England was still a feudal society where the King was the most powerful and owned all the land. The king distributed his land to the lords. This distributed land was known as fiefs. The nobles who received land from the king became his vassals and in return promised him their loyalty and service. The noblemen and their men at arms were obliged to fight in the King’s army and safeguard the crown. Homage was the process through which the lord or the noblemen became the King’s vassal. The land or fiefs given to the dukes, nobles, and lords were like small communities or villages. The Dukes lived in their manors or castles and kept 40% of the land to themselves. The remaining land was further distributed as fiefs to lords and nobles.

The serf was at the lowest level in the social hierarchy. They were labourers who had no material possessions and survived by working on the land in exchange for protection, safety, and subsistence from their lords. Feudalism gave absolute and hereditary power to the King, Duke, and the landed gentry. In case of a Duke’s or lord’s death, the land went back to the king and he redistributed it to other dukes, lords, or nobles.

The feudal society had a permanent class divide between the landowners such as the duke, and the tenants such as the knight and freemen. The Black Death and the Peasants’ Revolt caused a historic decline in feudalism.

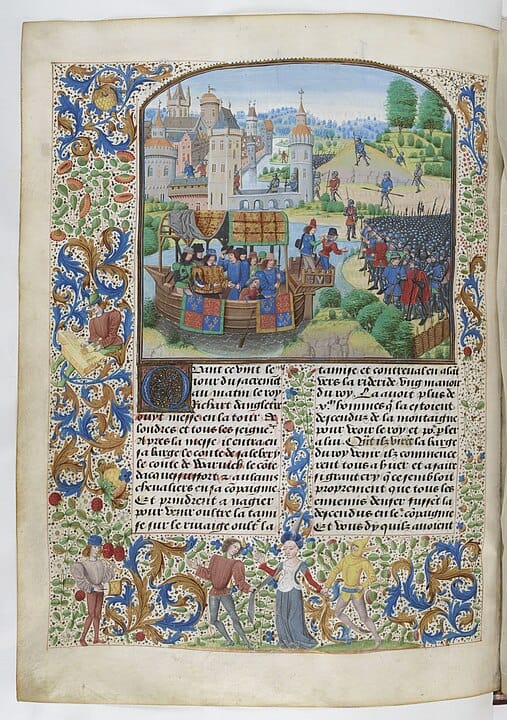

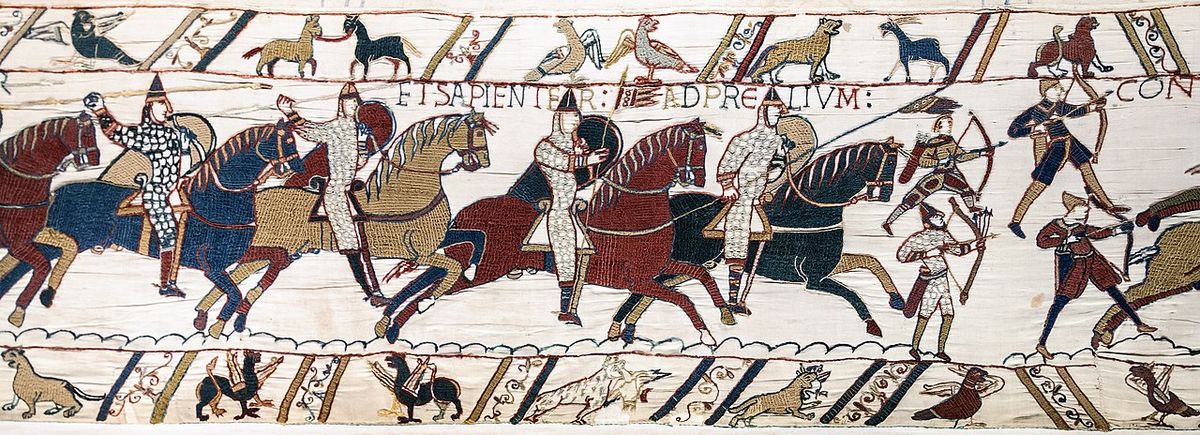

The Hundred Years' War

1337-1453

The Hundred Years' War was a collection of battles fought between the French and the English between 1337 and 1453. The English and the French often conflicted over land and power since the Norman conquest in 1066. The Hundred Years’ War was a result of several underlying causes.

- Conflict over the Duchy of Gascony: The English acquired the Duchy of Gascony through Henry II’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. Although the Treaty of Paris (1259) maintained peace between France and England for as long as 30 years, Gascony was often a source of contention between the two countries. In 1337, the French King Philip VI ordered the confiscation of Glascony. Even though no English king had visited the duchy since Edward I, its ownership was a critical cause of the Hundred Years’ War. The English aimed to get absolute power over Gascony without any French suzerainty. Gascony had significant economic advantages for England. It was a major source of trade that imported English grain and wool and exported wine to the country.

- Edward III’s claim to the French throne: Edward III’s mother Isabella was the daughter of Philip IV of France. This made him senior to the Valois line. Thus, Edward III could claim his right to the French throne. Although his claims were legitimate and strong, the French did not take them seriously. This might be because his inheritance was through a female line, and the French nobles preferred a Frenchman. Interestingly, in 1329, Edward III had even paid homage to Philip VI and acknowledged him as the French king at Amiens. Yet, when he had to justify the cause of war to the papacy in 1339, Edward III explained his legitimate claim to the French throne. Perhaps Edward III disliked being a vassal to the French king as the Duke of Gascony. Thus, the English claim to the French throne remained a persistent underlying cause of the Hundred Years’ War.

- Rivalries in the Low Countries: Edward III was married to Philippa of Hainault. Territories of Brabant and Jülich were also a part of the English empire. On the other hand, counts of Flanders and Artois owed homage to the French. Both France and England aimed to expand their territories into the Low Countries due to their economic significance and to fortify their political power.

- Scotland: The war between England and Scotland had broken out in 1296. During the reign of Edward II, the English were disastrously defeated by the Scottish King Robert Bruce. In 1333, the Scots were defeated by the English army led by Edward III and John Balliol, who had briefly been the King of Scotland in the 1290s. In the following year, there were several campaigns against the Scots. During this time, it was the French who gave refuge to David II, a young king of Scotland. In 1336, the English received an intelligence report about the French plans to support Scotland and attack Portsmouth. Thus it was clear that if Edward III wanted to succeed in Scotland, he would need to neutralize the French support for the Bruce monarchy. This further added to the friction between the French and the English.

- Presence of Robert of Artois in Edward III’s court: This was among the most immediate causes of the Hundred Years’ War. Robert was the brother-in-law of French king Philip VI. He was disgraced from the French court for forging documents to claim the county of Artois and had fled to the English court of Edward III. This support further infuriated Philip VI and acted as the last straw. In 1337, Philip VI confiscated Gascony and raided the English south coast the next year. Thus began a war that continued for a hundred years and had a lasting impact on the economy, society, and culture of both countries.

Impact of the Hundred Years’ War on the Age of Chaucer

The impact of the Hundred Years’ War can be summarised in the following points.

- The English lost all the French territories except for Calais.

- The Roman Church was considerably weakened as most of the French and English taxes went to military campaigns. This led to the creation of local churches.

- The landed aristocracy accumulated wealth and became richer, while the English monarchy suffered a continuous financial crisis.

- The lower sections of the society endured severe economic hardship. This was made worse by several taxes levied throughout the war.

- The wool and wine trade crashed.

- The English Parliament gained prominence in the nation’s political life.

The Hundred Years’ War left a lasting impact on the English economy, society, and culture. Although the war was a long one, it was not continuous. Additionally, most of the English army survived the war. The army that fought in the various battles of the war was as less as one-third or just half of one percent. Most men who participated in the war were noblemen or lords and Earls were prominent commanders. Going to war used to be a profitable occupation.

During the war, money came from several sources such as plunders, prisoners’ ransoms, and profits of office and taxes in occupied territories. The French did not gain much during the war because most of the battles were fought there. The English lost all the French territories except Calais but they were able to exploit them first. Most of the money was accumulated by the landed aristocracy. The gains from the war cushioned them against the impact of falling agricultural profits and fortified their stability.

The English nobility expanded significantly after the war. However, the expansion was not limited to heredity anymore. New members came through property ownership instead of inherited ranks.

Where the landed aristocracy became richer, the lower sections of the society had to endure severe economic hardships. As a result of the Hundred Years’ War, wool could no longer be exported from England and wine could no longer be imported from Gascony. This was extremely detrimental to the clothmakers. Similarly, merchants were severely impacted by pirates and the English army often called for the fishing boats. The region of Southampton was often raided by France. This economic crisis and unrest among the working class were further aggravated by the heavy taxes levied due to war and the Black Death in 1348.

The Hundred Years’ War also resulted in the development of a stronger Parliament in England. Due to the war, the English barons accumulated significant wealth by keeping it to themselves. On the other hand, the monarch continuously lost money. The king also could not levy taxes without the Parliament’s permission. Since the English monarch had to levy multiple taxes due to the war, the body was called upon several times. Even though the King was still the most powerful, the frequent meetings highlighted the presence of the Parliament. It became a part of the English political life. This was the beginning of a shift, a small dent in the absolute monarchial power.

The loss in the Hundred Years’ War forced the English to question the King’s divine right. The monarchy slowly but eventually had to relinquish its power. Fortunately, this also saved England from the fate of French royals during the Revolution. In contrast, the French monarchy became stronger after the Hundred Years’ War. The French King was free to levy as many taxes without any consultation. This eventually led to the French Revolution in the 18th century.

Before the Hundred Years’ War, French was the official language of the court. However, after the war, England became detached from the political affairs of mainland Europe. It developed a distinct English identity which was evident in the literary works of the Age of Chaucer.

The Black Death

1348

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that broke out in 1348. It wiped out nearly one-third of the English population and significantly damaged the established medieval feudal system. Since most of the English population succumbed to the plague, the demand and value for workers increased. The mass devastation caused by the plague also impacted the blind faith in the Church among people. In the longer run, the critical labour shortage and economic collapse that caused a decline in the feudal system resulted in greater freedom and autonomy among the working class.

The Peasants' Revolt

1381

Besides the Hundred Years’ War, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 was a major historic event during the Age of Chaucer. The war and Black Death (1348) resulted in a debilitating financial crisis for the peasants and the working class. To compensate for the rapidly depleting royal funds, the poll tax was imposed on all peasants above the age of 15, irrespective of their ability to pay.

The labour shortage caused by the Black Death significantly increased the cost of labour. To combat this, Edward III introduced laws that restricted the wages a worker could earn. This was known as the Statue of Labourers. Thus, the workers were unable to profit from their high demand and increased value. This created a sense of unrest among the working class.

King Edward III was succeeded by a very young king Richard II. Since the latter was a very young boy, England was governed by his uncle John of Gaunt who was particularly unpopular among the people. During this time, people had very little respect for the King and the government. After all, it was this government that had levied the Poll tax thrice, the third being higher than the previous two.

The peasants became increasingly anxious that the freedom and increased pay that they had finally begun to get would be taken away from them. The third Poll tax was particularly ruthless as it was levied per person instead of per property. Unrest was inevitable.

Priests such as John Ball preached that mankind was equal and encouraged the peasants to not remain tied to their land, church, or lords. In May 1381, the people of Fobbing refused to pay Poll tax and killed the King’s commissioners. Under the leadership of Wat Tyler, the revolt began in June 1381. The participants of the revolt demanded:

- Complete abolition of serfdom

- Repeal of labour laws that restricted the workers' wages after the Black Death

- Peasant participation in local government

- Redistribution of the Church’s riches

- Free fishing and hunting rights for all

Impact of the Peasants’ Revolt

Although Richard II promised important changes, he had no intentions of keeping them. He hung at least 150 rebels and displayed Tyler’s head on London Bridge. The Peasants’ Revolt failed but caused some social changes. The Poll tax was abandoned and the workers’ wages were no longer strictly restricted.

Religion in the Age of Chaucer

Clergy in the Age of Chaucer 1340-1400

The clergy in the Age of Chaucer mainly included priests who served the laity in churches and parishes within dioceses. Large cathedrals and churches received some land and revenue to support the education of priests. The clergy that was well educated held key positions in the administration of the State and Church. They also received some remuneration. Religious scholars were also employed as private chaplains, tutors, and assistants for both spiritual and temporal domains. The size and significance of the English clerical segment in the Medieval Ages was much greater than in any other period.

The clergy and laymen received primary education in small local schools after which they attended urban grammar schools. Further higher education in Cambridge and Oxford was pursued by few and through the financial aid of scholarships, gifts, and benefactions. Some advanced scholars also attended foreign universities. Since the education was primarily for the clergy, the main subjects used to be religion, courtesy, calculation, and the reading and writing of Latin. Most instructions were also in Latin. After university, the scholars filled the ranks of higher clergy and civil service. Those who did not finish college were employed to perform subordinate ecclesiastical and educational functions.

The main focus of the priest was to impart religious instructions to the masses, help them understand and practice religious beliefs, and observe their conduct and behavior.

Monks and Nuns

The main occupations of the monks and nuns were common worship and private prayer, study, meditation, singing, and saying Latin liturgy (mainly Psalms). They were not extremely educated and only a few had formal academic training. However, they knew some Bible and knew about the lives of saints, standard expositions of chief scriptural texts, and conventional teachings of Christian beliefs. Many monks and nuns in the richer abbeys and priories came from wealthy families. This was more so in the case of nuns rather than monks who often came from humble backgrounds.

The Friars

Besides monks and nuns, the friars or the mendicant was another important body of clergy, The friars had no material property or revenue. They survived on gifts and by begging. During the Age of Chaucer, they became prominent authors who popularised devotional lyrics, didactic poetry, and sermons in English. Even though friars were criticized for corruption and moral decay, they were a crucial element of the church and nation.

During the age of Chaucer, the majority of England was Catholic and most people were believers. Attending the church and unwavering reliance on their parish priest was prevalent. The church enjoyed a very significant position in people’s lives. They believed that the church was ‘the mother of us all’ and that her divinely appointed officers were her ministers on Earth. These ministers taught about the saints and the bible and were rarely questioned. Almost everyone knew the Apostle’s Creed, the Ten Commandments, the Pater, and the Ave. Prayers held a valuable position and people turned to the Church for everything- comfort, guidance, and assistance in crisis.

All significant religious works including the Bible was in Latin which was the language of all religious education and instruction. Thus, it was not directly accessible to the uneducated masses. The church was the only source of instruction, worship, and consolation. Since the church service used to be in Latin, hardly anyone could understand what it meant. The common people could only faithfully repeat their Aves and Paters without any substantial comprehension. The church attempted to explain the religious literature to the masses in various ways. It employed music, drama, imagery, and in most cases wall paintings. In bigger churches, rich glass paintings were also used. However, these also required a basic knowledge of religious scriptures. Thus, religious knowledge was restricted and enjoyed by the privileged few. Its access remained exclusively among those who knew Latin.

Towards the end of the 14th century, the Christian faith remained as strong as before but it began to need urgent reforms. Chaucer’s statement ‘if gold ruste, what shall Iron do?’ highlights the deterioration of the spiritual health among the clergy and the parish priests.

There existed stringent rules for monks such as commanding of claustration, prohibition of extravagance such as fur and gold, etc. Bishops often visited monasteries and nunneries to keep a check on their lifestyles. However, when William of Wykeham visited the priory of Selborne, he found that the monks were absent from their cloister, practiced hunting and sports, and even indulged in gold, fur, and frivolous conversation. Similar spiritual decay and corruption was observed by Bishop Alnwick during his visit to the Lincoln diocese.

This monastic decay became the raw material for Chaucer in his portrait of the monk in the Canterbury Tales. The prevalent religious corruption and power abuse are further critiqued in the works of Langland, Gower, and Wyclif. Wyclif points out

“four or five needy men might well be clothedwith one cope and hood of a monk, and that large cloth serveth to gird wind and prevent him to go and do his deed’’

If the monks were corrupt, the friars were worse. Their greed for money, unscrupulous practices, shameless indulgence in luxury, and easy penances are often exposed and critiqued in the literature belonging to the Age of Chaucer.

Kings in the Age of Chaucer

Edward I - 1272-1307

Popularly known as the hammer of Scots for defeating Scotland, Edward I was responsible for forming the Model Parliament in 1295. He was the first monarch to include the members of the nobility and the church.

Edward II - 1307-1327 (deposed)

He was a weak and incompetent king whom the barons particularly hated due to his favoritism towards Piers Gaveston. He was deposed in 1377.

Edward III - 1327-1377

Edward III is well known as the monarch who began the Hundred Years’ War by declaring himself the King of France. He wanted to conquer France and Scotland. The reign of Edward III was marked by the devastating Black Death and military setbacks in the war.

Richard II- 1377-1399 (deposed)

Richard II faced a historic rebellion from peasants dissatisfied with the heavy taxes and social conditions. It was under his reign that the Peasants’ Revolt began. Richard II also faced challenges from powerful nobles who often questioned his authority. This led to periods of political instability.

Henry IV- 1399-1413

Son of John of Gaunt, Henry IV was the first ruler of the House of Lancaster. His accession to the throne ended the rule of the House of Plantagenet. He returned to England from his exile in France and usurped the English crown from Richard II through several political maneuvers. Henry IV is featured in Shakespeare’s historical plays ‘Henry IV, Part 1’ and ‘Henry I, Part 2’.

References

Cartwright, Mark. "Causes of the Hundred Years' War." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 05 Mar 2020. Web. 24 Feb 2024.

Cartwright, Mark. "The Hundred Years' War: Consequences & Effects." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 06 Mar 2020. Web. 23 Feb 2024.

Cartwright, Mark. "Peasants' Revolt." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 23 Jan 2020. Web. 24 Feb 2024.

Ford, Boris. The Pelican Guide to English Literature: The Age of Chaucer. 1965.

Henry Stanley Bennett. Chaucer and the Fifteenth Century Verse and Prose. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1990.

Johnson, Ben. “Kings and Queens of England & Britain.” Historic UK, www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/KingsQueensofBritain/.

Prestwich, Michael. A Short History of the Hundred Years War. I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2018.

World History Encyclopedia. “What Was Feudalism in Medieval Europe?” YouTube, 8 Apr. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Whvf2EPe-g

Read More in English Literary History

Anglo Saxon Literature

Anglo Norman Literature

Anglo Norman Historical Background

Latest on Literary Theory

Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

Dialectics

Basics of Marxism

About Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play

The Nature of the Linguistic Sign

Langue and Parole

Toward a Feminist Poetics by Showalter

Gynocriticism