The Age of Chaucer & His Works - A Critical Analysis

The 14th-century English literature is popularly known as the Age of Chaucer. This is because Geoffrey Chaucer was the greatest and most resourceful poet of his time, so much so that he was regarded as the founder of English verse by John Dryden (1631-1700).

Popularly known as the founder of modern English and the Father of English literature, it was because of Chaucer that the middle English became a respectable medium for literature. Besides coining various words such as bribe, femininity, plumage, etc, he also invented Rime Royal, a seven-line iambic pentameter stanza.

Professor John Livingston Lowes perfectly summarises the significance of Chaucer when he says:

“He had, to be sure, “no message”. But his sanity (“He is”, said Dryden, “a perpetual fountain of good sense”), his soundness, his freedom from sentimentality, his balance of humorous detachment and directness of vision, and above all his large humanity - those are qualities which “give us”, to use Arnold’s own criticism, “what we can rest on” ”.

Geoffrey Chaucer: Early Life and Influences

Chaucer (1340s - 1400) was a worldly man exposed to diverse people from different walks of life. He was born to a wealthy family of vintners - his grandfather (Robert Chaucer), step-grandfather (Richard), and father (John Chaucer) were all wine merchants. In fact, his father, John Chaucer was a customs officer responsible for collecting duty on wines at various southern ports, and had a significant place in London’s social life. As the son of an influential vintner, Chaucer was often exposed to men from overseas and their strange foreign stories since childhood. This early exposure is a crucial factor that makes Chaucer a distinctly better poet than his contemporaries Langland or Lydgate who were constrained by their limited education and opportunities. Langland’s passionate and violent attitude is in sharp contrast to Chaucer’s worldly and patient outlook that was shaped during his childhood.

During his early years, London was Chaucer’s school. The bustling city was full of shipmen and pilgrims, and a highly cultured and cosmopolitan French society.

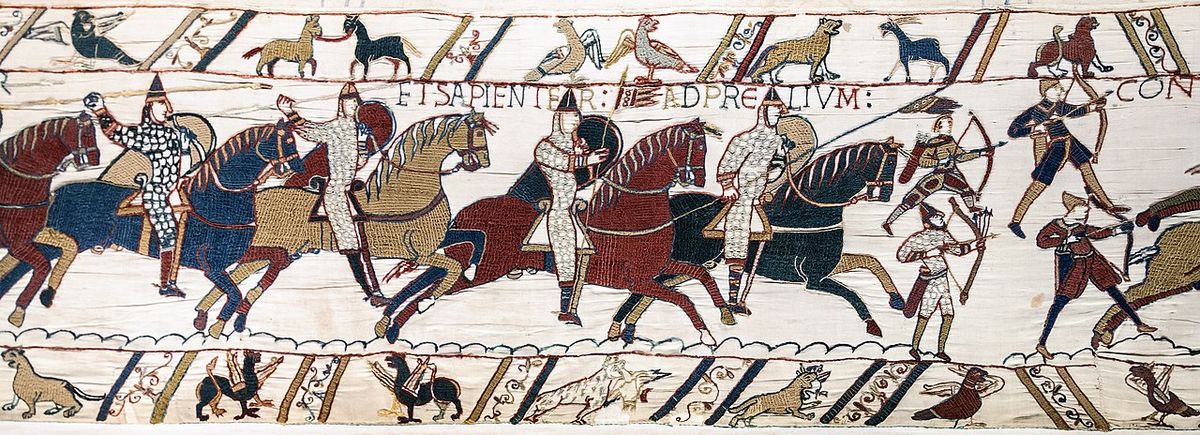

Chaucer also worked as a page in the service of Elizabeth of Ulster, the wife of Edward III’s son Lionel. During his service, he was exposed to the courtly life. In 1359, he was a part of Edward’s invading army in France and was taken as a prisoner. The king ransomed Chaucer and he returned to England in 1360. In the autumn of the same year, he was again in France. These events further enriched Chaucer’s experiences and contributed to a cosmopolitan mindset.

In 1367, Chaucer received a pension as the groom or yeoman in the royal household and was described as “dilectus vallectus noster” or ‘our beloved yeoman’. Around this time he also married Philippa, sister to Katherine Swynford, who was once the wife of John of Gaunt and was in the Queen’s service.

Impact of French Poetry on Chaucer

Roman de la Rose, Machaut, Guillaume de Lorris, and Jean de Meun

Chaucer’s earlier works reflected his experiences at the royal court. It is for such “many a song and many a lecherous lay” that he apologises for during his last years. Most of his works during the early years were focused on winning the favours of ladies. It was during this period that Chaucer translated Roman de la Rose. This French poem was one of the most popular, significant, and influential works for both the English and the French. Undoubtedly, it influenced Chaucer too. Throughout his early poems, there is an evident influence of Guillaume de Lorris. However, in his Canterbury Tales, it is the satirical and realistic Jean de Meun whom Chaucer turns to for both methods and models.

French poetry, literature, and culture had a significant impact on Chaucer. He was particularly influenced by the works of Machaut. Most of his early works were heavily influenced by the French poet. The Book of the Duchess is one of Chaucer’s finest tributes to his French influence and learning.

The Death of Blanche the Duchess or The Book of the Duchess (composed around 1368-1372)

Duchess Blanche was the first wife of John of Gaunt who died in September 1369. It was her death that caused Chaucer to compose The Death of Blanche the Duchess or the Book of the Duchess. The poem showcases how dependent Chaucer was on the French and Latin models and how he heavily borrowed from Guillaume de Machaut, an influential French composer and poet. He adheres to the established conventions of the allegorical dream poem. However, at the same time, he also utilises it uniquely to highlight the pathos of his story. Chaucer was fascinated by dreams and attempted to use the strange events in dreams as his material in the Book of the Duchess.

Even though the poem appears to be simple, it is a much more complex work that would have required thorough readings of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Dit de la Fontaine Amoureuse and Le Jugement dou Roy de Behaingne by Machaut, and Paradys d’ Amours during composition. Chaucer blended these works masterfully and composed a poem that became distinctly his.

The Book of the Duchess is structurally flawed. The story becomes a little too lengthy before its climax which is abruptly concluded. Moreover, there are several repetitive elements such as the personification of Love and Nature, the dream convention, and a sleepless reader.

Despite these shortcomings, the poem has remarkable merits. It showcases Chaucer's growing knowledge and experiences. The death of Duchess Blanch equips him with the personal experience that he distinctly infuses into an elegiac poem. The poem explores the profound grief of a husband who has lost his beloved wife. Chaucer elevates this grief through his lively description of the duchess - her sweet disposition, and femininity.

Till 1370, most of Chaucer’s works, although significant, were nothing more than promising. By this time, he had acquired a wealth of worldly knowledge and experience as a rich vintner’s son, a yeoman in the King’s court, and as a soldier in Edward III’s army. Besides these first-hand experiences, Chaucer also had formal learning of Latin that introduced him to Virgil, Ovid, and all the mediaeval Latin classics.

Chaucer's Life at Court

The years 1370-1380 were the most important in Chaucer’s life. During this time, he became the Esquire of the Royal Household. This was a particularly interesting position as it enabled Chaucer to meet and observe various influential men in culture. Being in the service of the King, he frequently came in contact with London’s men of importance, continental diplomats, and even rulers. Thus, Chaucer enjoyed a rich and diverse social circle. From this society and contacts, Chaucer inculcated a distinct knowledge of humanity that became a characteristic feature of his writing.

Employed as a royal esquire, Chaucer had to demonstrate proficiency in almost everything, or at least maintain such an impression. He was expected to be able to dance, sing, recite poetry, entertain, as well as conduct dignified and serious activities with equal efficiency. Most importantly, he was frequently at the service of ladies. His exposure to the royal female society helped him create numerous detailed and remarkable lifelike feminine portraits that were, unfortunately, lacking in most romantic heroines. He was not restricted to partial access to high society through just reading books or distant observations, instead, he was right in the middle of it. This experience reflects in his Book of the Duchess. His in-depth portrait of the lady Blanche is the most outstanding feature of his work. In his later works too, he continued to uniquely blend the conventional literary models with his personal knowledge and experience which had never been done before in romance.

The Italian Influence

Frequent travelling shaped Chaucer’s knowledge to a great extent. Between the years 1370 to 1378, Chaucer visited France, Flanders, and Italy. While France was already familiar and important to him through previous trips and literature, Italy too made a lasting impact on Chaucer and his art. Even though the natural landscape was only a background in the Age of Chaucer, it was still an impactful factor in a poet’s life. In Italy, Chaucer enjoyed the breathtaking Italian landscape and cities that blended their Roman past with the present. Italy was a historically, architecturally, and culturally invigorating country that must have immensely excited and interested Chaucer as an artist. During Chaucer’s stay, Italy was politically unstable and frequently broke into violent disputes. The poet also met the most powerful Italian tyrant Bernabó Visconti who had married his niece Violanta to Lionel, son of Edward III.

Besides the trips to Italy, the literary works of Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch immensely influenced Chaucer who was proficient in Italian.

During the years 1374-1386, Chaucer was the Controller of the Customs and Subsidies on wool, hides, and sheep-skins in London’s port. This job rewarded him with a pension from John of Gaunt, a pitcher of wine, and a rent-free house above Aldgate. He spent his tenure in frequent diplomatic and business travels. During this time, he also came in contact with the most powerful and influential men in London and came to know about the world through them. This knowledge was not just limited to England or the continent, but beyond it.

Chaucer was a well-read and well-travelled man who frequently met a variety of people who told him a variety of stories. All of these factors shaped his works. For instance, his conversations with the knights and their followers informed him about the ongoing affairs in Europe.

While staying at Aldgate, Chaucer spent the rest of the time honing his craft. He read the works by French and Italian poets and attempted to adapt them into English verse. This resulted in some of his finest works - House of Fame, the Parliament of Fowls, and Troilus and Criseyde.

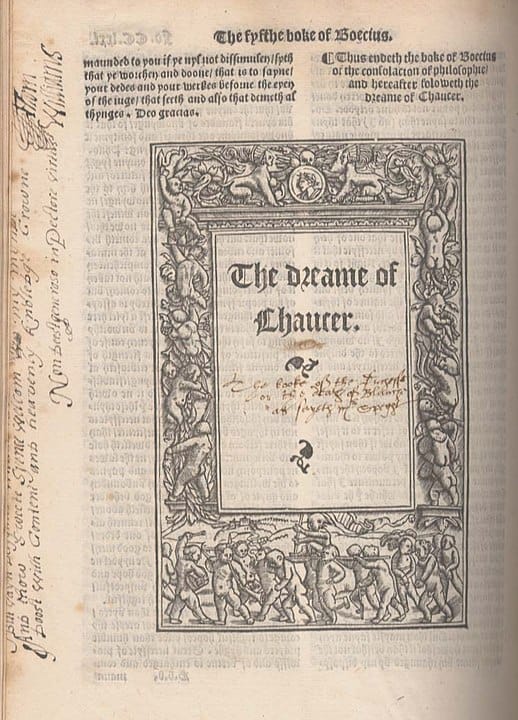

The House of Fame

Composed around 1378-1386

Genre: Dream Vision

Metre: Octosyllabic

The House of Fame is one of Chaucer’s finest earlier works that showcases his attempt at incorporating the elements of both French and Italian poetry. Even though he was completely comfortable with French poetry, he had begun to explore Italian poetic sensibilities. Just like the Book of the Duchess, the poem is another dream vision. Interestingly, it is unclear why Chaucer wrote it, and is left incomplete. Nevertheless, it is one of the most charming and original works by the poet.

The poem is influenced by the works of Ovid, Virgil, Macrobius, Alanus de Insulis, Froissart, Dante, and Boccaccio. Nevertheless, Chaucer uses these inspirations and makes his poem completely original. The invocations in Book II and Book III evidently imitate Dante’s Divine Comedy. However, since the poem has a drastically different subject matter, there is not much direct imitation. Influenced by Dante in the House of Fame, Chaucer goes beyond the conventional and dominant eroticism of French poetry.

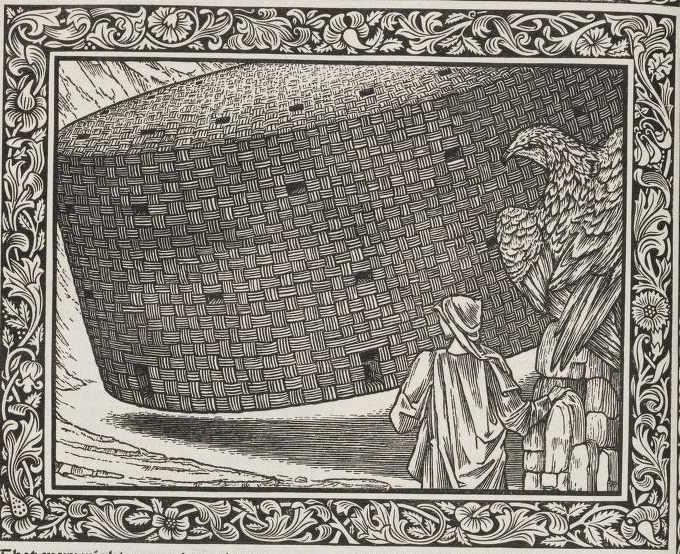

The Book is divided into three Books. In Book I, the poet narrates a dream he dreamt on the 10th of December. In his dream, the poet finds himself in a magnificent glass temple adorned with rich shrines, golden images, and ancient statues. He then gives an elaborate account of the Aeneid which becomes almost too lengthy for modern readers. The poem becomes extremely interesting with the arrival of the Eagle towards the end of Book I.

Book II includes a lively and comical portrayal of the Eagle who talks to and pacifies a terrified Chaucer. This portrayal and dialogue is exceptionally distinct to Chaucer and his works. Chaucer arrives at the House of Fame and it is here that he is at his imaginative best.

Book III of the poem vividly describes the House of Fame and how the poet encounters the figures of famous magicians, enchantresses, witches, scholars, and illusionists. He finally enters the hall of Lady Fame who is surrounded by people aspiring for fame. While she grants the wishes of some, she rejects the others. The poet is led outside the House of Fame and to the House of Rumour by a stranger. This house is 60 miles long and is made of twigs. It has several entrances and even has holes in its roof. Even though there are no doors at any of the entrances, It is extremely difficult to enter this house as it is constantly whirling. The Eagle arrives again to Chaucer’s rescue and places him inside the house. There, Chaucer is able to hear all sorts of rumours, gossip, and conversations about life, loss, love, sickness, victories, folktales, etc. The poem abruptly ends with Chaucer encountering a man of great authority and power.

Chaucer displays acute observation and attention to detail that successfully evoke excitement and bewilderment throughout the poem. Several elements such as the detailed and elaborate descriptions of the House of Fame and Rumour, and the lively and crisp conversation between the Eagle and Chaucer make House of Fame a distinct poem, a kind that had never been written in English before.

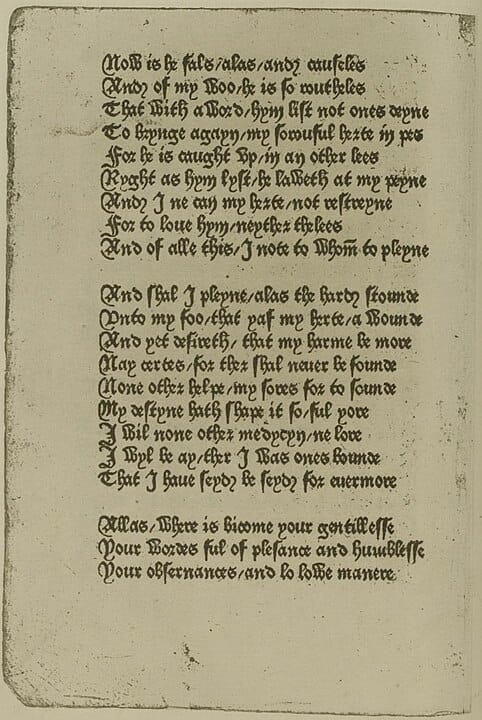

Anelida and Arcite (1380-1386)

Anelida and Arcite - Chaucer's Original Manuscript

Popularly also known as the preface to the Knight’s Tale, Anelida and Arcite is an extremely short and incomplete poem. Its story is based on Boccaccio’s Teseide and is another example where Chaucer experimented and combined conventional French as well as Italian poetry. He attempts to frame a traditional French complaint poem within a heroic setting. Although complex, the rhyme scheme of the poem has a fluidity that marks an advancement and improvement in Chaucer’s poetic art.

Parliament of Fowls (Parliament of Foules)/ Parlement of Briddes/Assembly of Foules

Composed around 1380

Genre: Dream Vision

Metre: Rhyme Royal - Chaucer introduced rhyme royal to English poetry.

The poem is among the earliest references to St. Valentine's day as an occasion for lovers.

Another dream vision by Chaucer, the Parliament of Fowls consists of many conventional elements and will even remind the readers of the Book of Duchess - the poet reading before falling asleep, the dream arising from the book’s subject matter, and the occasional appearance and disappearance of supernatural and natural elements. Just like his previous works, Chaucer uses several works by French, Italian, and Latin authors as his source material and utilises them distinctly in this poem. Despite all the borrowings, the Parliament of Fowls is fresh and unmistakably by Chaucer.

The poem begins with Chaucer reading Cicero on the Dream of Scipio which deals with Scipio’s arrival in Africa and falling in love with Massinssa. At night, he dreams of his grandfather who shows him heaven and reveals how virtuous people will end up there. Eventually, as the night falls, the exhausted poet falls asleep and has a dream vision.

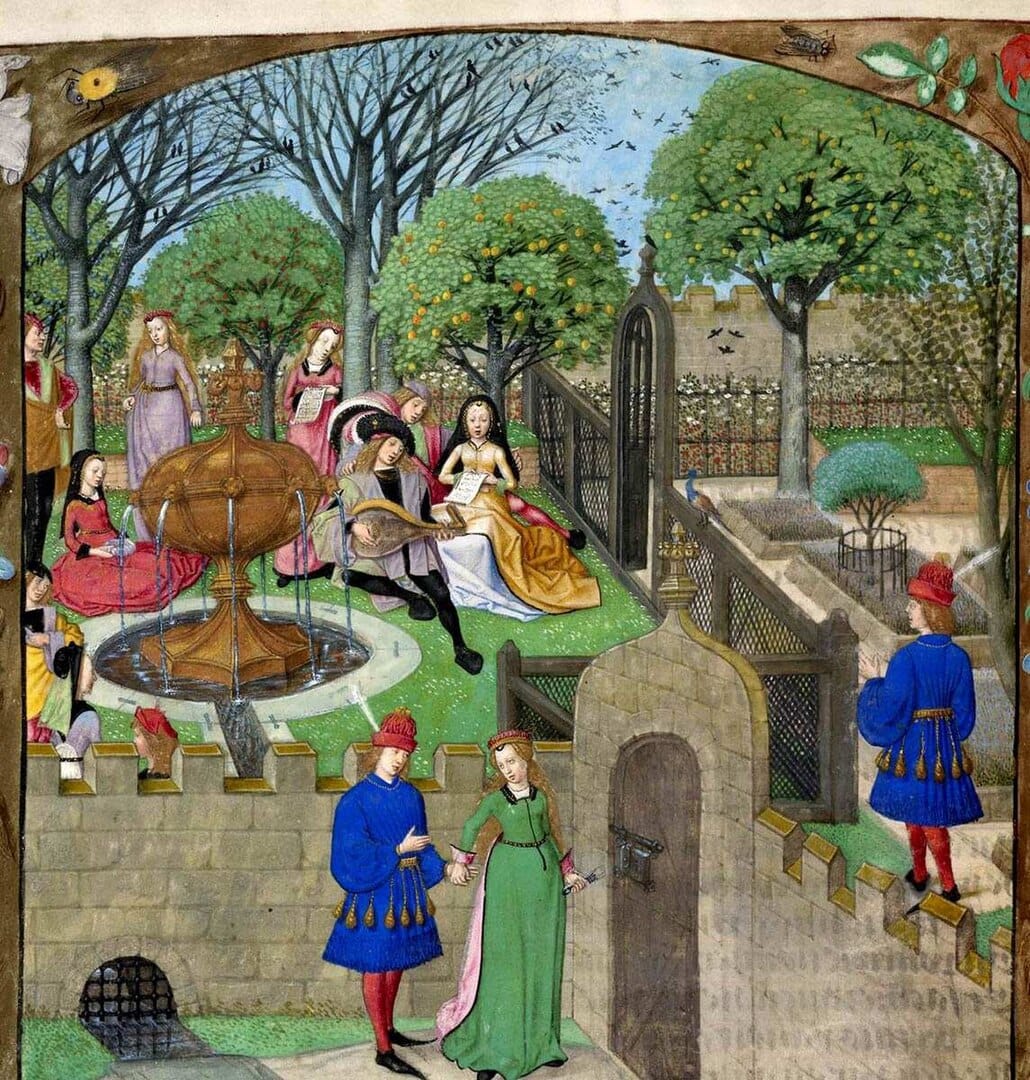

In the poet’s dream, Scipio’s grandfather leads him through the gates of a blissful place where there is perpetual May (spring), infinite greenery, and joy. As the poet roamed about, he came across Goddess Nature around whom birds were assembled in a particular order - the birds of prey were perched the highest, while the birds who ate seeds were at the lowest level. It is St. Valentine’s Day, and the birds are assembled to select their mates. This unique scenario in the poem is distinctly Chaucer’s original creativity. Even though the topic is not grand and noble, the poet treats it with an unprecedented freshness.

Goddess Nature asks the first male eagle to select his mate. The male eagle chooses the formel eagle perched elegantly on the Goddess’s arm and eloquently declares his love for her. However, two other male eagles declare their love for the same female eagle and begin to contest each other. This makes other birds impatient and their protesting cries fill the forest air. This whole scenario where the birds voice their impatience is particularly comical and something that had never been created in English poetry before. Chaucer masterfully imparts individuality and personality to each bird. The order of birds and their life-like portrait appears like an early version of The Nun's Priest's Tale. The status of birds can also be interpreted as the depiction of societal order. Chaucer was increasingly inclined to depict his contemporary society. This is evident in his critical treatment of the ideals of courtly love. He exhibits a mature detachment throughout the poem which was his distinct characteristic.

The octosyllabic stanzas are replaced with more flexible seven-line decasyllabic stanzas. The poem is among the first of Chaucer’s works that adopted the rhyme royal rhyming stanzas.

The Parliament of Foules concludes with the Goddess Nature granting the female eagle a year to decide and choose one of the three eagles as her worthy mate.

Troilus and Criseyde

Composed around 1382-1386

Genre: Epic poetry, Courtly romance

Metre: Rhyme Royal

Original Source: Filostrato by Boccaccio

Besides the Canterbury Tales, Troilus and Criseyde is one of the finest works belonging to the age of Chaucer. Chaucer’s journey to Italy significantly impacted and shaped his poetry. He returned with the manuscripts of Dante’s Divine Comedy and Boccaccio’s Filostrato, and must have also read Petrarch. It is Filostrato that became the source of one of his best works - Troilus and Criseyde.

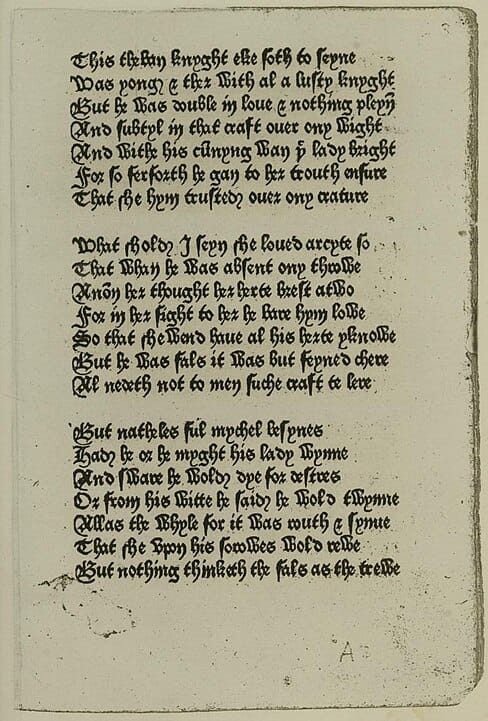

In this poem, Chaucer expanded Filostrato from 5,704 lines to 8,239. In this process, he granted its three main characters a distinct individuality and created his unique version that goes beyond the Italian source. Chaucer was intimately familiar with courtly love traditions as well as individualistic passions. This resulted in lifelike distinct characters of Pandarus, Troilus, and Criyseyde.

In Boccaccio's Filostrato, these characters were portrayed well but were strictly conventional- Troilus was the idle, passionate spoilt young man with the sole aim of fulfilling his immediate desires; Pnadarus, Criseyde’s cousin was a similar young man whose main duty was to help Troilus get the woman he desired and be the confidant; Criseyde was a beautiful but faithless woman who was the beloved and the object of desire for Troilus. Undoubtedly, Boccaccio portrays these characters beautifully despite having little substance to work with. It is here that Chaucer saw scope and an opportunity to create his original work.

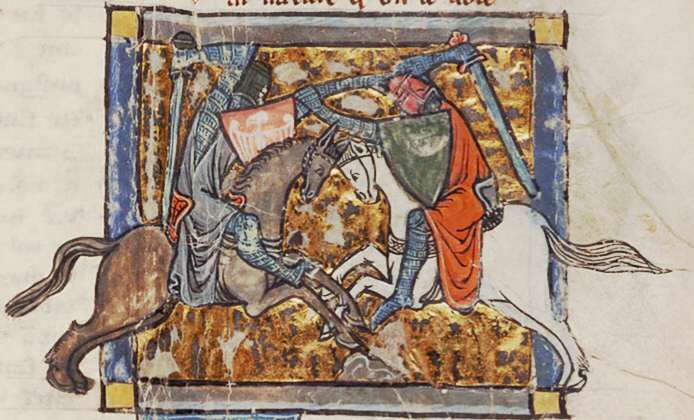

While Boccaccio focused on the story, for Chaucer the characters take centre stage. In Troilus and Criseyde, Troilus, Criseyde, and Pandarus are no longer one-dimensional stock characters. Instead, they become multifaceted individuals. It is on the shoulders of the sophisticated and nuanced portrayal of these characters that Chaucer is able to compose a lengthy poem of more than 8000 lines. Troilus is no longer a frivolous character but is also portrayed as a warrior. Chaucer creates these individuals in a way that justifies the intense pity the poem evokes among the readers towards its end.

Even though the chivalric code had become obsolete in the age of Chaucer, the poem still accepts the code and includes some of its elements - love being in the hands of destiny; absence of love in marriage; absolute fidelity; and secrecy of love. This is why Troilus pines for Criseyde. However, Chaucer never fails to convince us that behind these conventions is an individual man.

Similarly, Criseyde is not simply a beautiful, shallow, and faithless woman. It is through her sophisticated character that Chaucer achieves the prime of his creative power. Since her father Calchas had fled as a traitor, her state in Troy was extremely vulnerable and she was constantly anxious about the outside world. This was Criseyde’s state of mind when her uncle Pandarus comes to speak about Troilus’s love for her.

Chaucer very successfully portrays Criseyde’s complex state of mind. She does not fall in love with Troilus immediately but is eventually moved by his devotion and masculinity. She is far from a shallow woman without any substance. Chaucer gloriously depicts all her shades - her pride in being Troilus’s chosen one in all of Troy, her vanity about being the most beautiful woman in Troy, her apprehension about losing her freedom to love, her anxiety and awareness of the prevalent gossip. The readers understand what leads Criseyde to accept Troilus’s love.

At the Greek camp, Criseyde is all alone in a foreign land. Even here, Chaucer effectively reveals the conflict and emotional struggles that Criseyde has to endure alone. Eventually, she gives in to Diomede. Chaucer carefully creates Criseyde’s character and constantly attempts to defend her actions throughout the poem. She has to face circumstances that can test even the strongest of characters. Being a woman of dependent, amorous, and timid nature, Criseyde stands no chance of enduring an isolated burden. However, Chaucer refuses to depict her as a conventional shallow, and shameless lover.

The character of Pandarus too is not limited to simply being Troilus’s friend who helps him fulfil his desires. He is also Criseyde’s uncle, someone who should have protected her from such lovers’ advances instead of encouraging and advocating for them. Pandarus is a major cause of Criseyde's misfortune. He religiously follows the code of chivalry and devotes himself to Love. For twenty years he has been in unreciprocated love with a lady. Thus, when Troilus is in love, Pandarus is not only motivated to help his friend but is also bound by his service to Love. He becomes a confidant who understands the pain of unrequited love and thus pleads with Criseyde.

In the case of Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer was fascinated with the characters and it is through his masterful portrayal of Troilus, Criseyde, and Pandarus that the poem becomes one of his most celebrated works.

While Chaucer was composing Troilus and Criseyde, he was writing in the court of Richard II. Thus, some elements were particularly included to meet courtly demands. For instance, lengthy discussions on predestination in Book IV.

Chaucer not only wanted to compose a poem rooted in traditional courtly love that had become irrelevant to most of his audience. He also wanted to mould his characters in a way that revealed their innermost emotions, vulnerability, and feelings. With Troilus and Creseyde, he pays homage to all the worldly pleasures but does not forget to highlight their ephemerality.

The Legend of Good Women

Composed around 1385-87

Genre: Love-vision

Metre: Iambic Pentameter

After Troilus and Criseyde and before composing his magnum opus the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer wrote the Legend of Good Women. This incomplete poem was a transitional work in several ways. The poem is the last of Chaucer’s love visions and the very first work in English that used the iambic pentameter. By this time, Chaucer had become an adept poet who knew how to utilise conventional traditions and sources and create something distinctly his own.

The prologue has two versions- the F and the G versions. In the prologue, Chaucer dreams of the God of Love and Lady Alceste. The God of Love chastises him for writing women in poor light in his Troilus and Criseyde and The Book Of Duchess. In both his works women cause the men great sorrow by not reciprocating their love and devotion. Lady Alceste tries to save Chaucer and orders him to write about women with unshakable devotion to love. The Prologue is one of Chaucer’s most intimate and finest works where he creates a mosaic of adaptations from French and Italian authors such as Froissart, Deschamps, Machaut, and Boccaccio.

The poem includes nine sections and has the legends of ten virtuous women - Cleopatra, Thisbe, Dido, Hypsipyle and Medea, Lucretia, Ariadne, Philomela, Phyllis, and Hypermnestra (incomplete). All nine tales are about devoted women who were wronged and abandoned by men they loved.

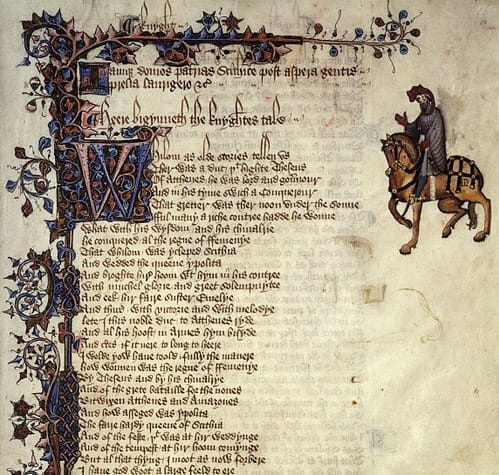

The Canterbury Tales

Composed around 1387-1392

As discussed before, Chaucer was a significant man in his society. He frequently received wardships and gifts from the royal household. In 1386, he left Aldgate, moved to Kent, and became a member of parliament. In 1389, he received the most powerful and responsible position of his life when he became the Clerkship of the King’s Works. It must be during this time that Chaucer thought about the Canterbury pilgrimage and began writing the Canterbury Tales.

The idea of a pilgrimage was perfect as it provided the best setting to let Chaucer bring together diverse characters for a shared purpose. The pilgrim also allowed these people to lower their guards and strict conventional etiquette that they had to abide by in everyday social life. The Canterbury Tales gives us the privilege of access to 14th-century men and women. This access is not limited to a formal and frigid tapestry but becomes a lively portal to their individual personalities as they laugh and talk.

Chaucer’s general plan for the Canterbury Tales was that each of the thirty pilgrims would tell two stories during their journey to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket in Canterbury, and two more stories during their homeward journey. The pilgrim with the best story would win supper at the Tabard Inn near London and the host, Harry Bailey was the master who would decide the winner. Thus, the initial plan included at least 120 stories. Nevertheless, Chaucer was unable to carry out his original plan.

The sequence of the stories in the Canterbury Tales is natural and chaotic just like life itself. As the Knight completes his story, it must be ideally the Monk’s turn to narrate his tale. However, the drunk Miller interrupts and begins with his story instead. This natural human interruption makes Chaucer’s work stand out from conventional mediaeval poetry of his age. Throughout the Canterbury Tales, the pilgrims are not limited to just stories but frequently erupt in banters and character-revealing commentaries.

The Canterbury Tales include almost all facets of English life and society. However, some sides, such as the peasant life, do not occupy any significant space in the poem. Peasant life in the fields was a significant part of mediaeval English society and is depicted in Piers Plowman and many other mediaeval poems. However, Chaucer skips this popular mediaeval element. Villagers who appear in the Canterbury Tales are aristocrats.

Throughout the poem, varied worlds collide - the grave and gay, supernatural and worldly, all amalgamate and create an outstanding world. Throughout the tales, Chaucer is continuously excellent at his craft. His genius lies in the combination of his remarkable poetic sensibilities and his acute understanding of men and women. While Chaucer exhibits a remarkable understanding of human character, he also demonstrates remarkable tolerance and distance. While his contemporaries like Gower, Langland, and Wyclif are driven to frequent emotional and violent outbursts at the mention of corrupt monks, friars, and idle beggars, Chaucer remains detached. He almost possesses a Shakespearean ability to accept life as glorious and as ugly as it was without any prejudice or resistance.

All of the poet's phases and experiences as a vintner’s son, page, esquire, ambassador, controller of customs, clerk of works, and sub-forester culminate into the creation of his masterpiece, the work he is known the most for- the Canterbury Tales. There had been no side of the English society that Chaucer was unfamiliar with. Moreover, the exposure to French and English poetry honed his poetic artistry and enabled him to experiment with metres and poetic forms. Combining his personal diverse social experiences and a deep insight into human nature with a rich poetic knowledge, Chaucer became the poet who is rightfully the representative of the 14th century - the age of Chaucer.

List of Works by Geoffrey Chaucer

Major works by Geoffrey Chaucer include

- Translated Roman de la Rose as the Romaunt of the Rose

- ABC

- The Book of the Duchess

- The Complaint unto Pity (lost)

- The Complaint to His Lady (lost)

- The Complaint of Mars

- The Complaint of Venus

- The House of Fame

- Anelida and Arcite

- Saint Cecelia

- The Parliament of Fowls

- Boece (Chaucer's translation of Boethius's The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius)

- Troilus and Criseyde

- Palamoun and Arcite (later used as the Knight's Tale)

- The Legend of Good Women

- The Canterbury Tales

- Treatise of the Astrolabe

- The Envoy to Bukton (The reader is urged to read the Wife of Bath

- Complaint to His Purse

The Age of Chaucer & His Works: Citations

“A Brief Chronology of Chaucer’s Life and Times.” Chaucer.fas.harvard.edu, chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/brief-chronology-chaucers-life-and-times-0.

Bennett, H. S. Chaucer and Fifteenth-Century Verse and Prose. 1947. Clarendon Press. Oxford, 1990.

Daiches, David. A Critical History of English Literature. Allied Publishers, 1979.

Piero Boitani, and Jill Mann. The Cambridge Companion to Chaucer. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Sanders, Andrew. The Short Oxford History of English Literature. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Read More on Literary History

Anglo Norman Period in English Literature

Anglo Norman history

Ango Saxon Literature

Read More on Literary Theory

Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses by Althusser

Basics of Marxism

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play

Toward a Feminist Poetics by Elaine Showalter

Gynocriticism

Nature of the Linguistic Sign