Derrida’s Structure, Sign and Play - Summary and Analysis

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) presented ‘Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’ in an international symposium ‘The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man’ hosted by the John Hopkins University in 1966. Among the prominent structuralists who attended and contributed to the symposium were René Girard, Lucien Goldmann, Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Richard Macksey, and Eugenio Donato. Eventually Derrida included this lecture as an essay in his later work ‘Writing and Difference’ that was published in 1967. This blog attempts to simplify Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play and includes:

- Popularity of Structuralism

- An academic background to Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play

- Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences- summary

- Key Ideas of Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play

Popularity of Structuralism

The very first thing we must keep in mind while reading Derrida’s Structure, Sign and Play is its core focus on Structuralism. In this seminal essay, Derrida presents a complex idea that human knowledge and meaning must not be founded on, or centered in language. Derrida arrived at this idea through his understanding of a popular school of thought known as “structuralism”.

Basics of Structuralism

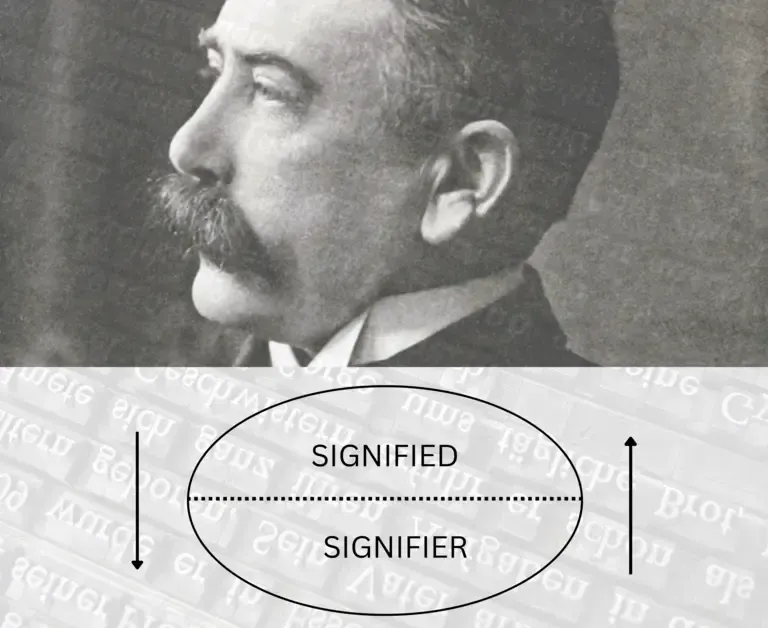

Structuralism is a way of understanding how meaning is produced. As a methodology, it was developed from the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure presented in Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale). According to Saussure, the basic unit of language was "sign". This elementary sign consists of two inseparable elements- "signifier"- which is the word or the sound image, and "signified"- which is the concept linked to the signifier or the word or the sound image. For example, in the English language the sign "flower" consists of the sound image or the word "f-l-o-w-e-r" and the concept flower.

According to Saussure, words or signifiers were related to reality through linguistic rules and conventions. For example, if we come to think of it, there is no actual link between the word “flower” and the actual flower, or the word “book” and the actual book. They are known as flower and book just because English speaking people call them so. Thus, we can conclude that the meaning of the word “flower” is because of its place in the “structure of the English language. Thus a linguistic sign is arbitrary

Another important thing that Saussure noted is that we identify the actual flower from its signifier “flower” because its meaning is different from other words. In simple words, the meaning of the term “flower” is different from the meanings of the terms such as “bud”, “bouquet”, “plant”, “shrub”, etc. We know that a flower is a flower because it is not a bud, a shrub, a plant, or a bouquet. The meanings of all these terms are different from a flower. Similarly, we know that the meaning of the word “book” implies the actual book because its meaning is different from that of pamphlet, diary, notebook, papers, etc. Our knowledge and understanding of the English language help us identify the differences of the meanings of words. This is how we derive meanings. Thus, according to Structuralism, meaning in a language is derived from webs of differences within a structure.

Saussure implemented these ideas beyond linguistics and founded semiology, a study of signs within a society. Structuralism employed the above concept of how meaning is generated to various fields such as literature, anthropology, sociology, and philosophy. It focused on how meaning was generated and understood, and attempted to find its fundamental structures. Thus, after the 1940s, structuralism became extremely popular school of thought in human sciences.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play is influenced by the Ferdinand de Saussure, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Martin Heidegger.

An Academic background

to Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play

As the title suggests, Derrida’s ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences’ is not exclusively a literary theory but also concerns with human sciences such as linguistics, anthropology, philosophy, and literature. Structuralism developed by the works of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure had already begun to dominate human sciences. By the year 1960, Structuralism had become the most popular and important theory in continental Europe. Despite its immense popularity, structuralism was still perceived as a new and experimental movement. Its validity still required to be established and assessed. It was with this aim that Johns Hopkins University hosted a symposium “The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man” in 1966. This symposium was attended by many prominent and seminal structuralist thinkers who attempted to examine and discuss structuralism and its impact on human sciences. Besides Derrida’s Structure, Sign and Play, some other contributions in the symposium include:

- 'Lions and Squares: Opening Remarks' by Richard Macksey

- 'Tiresias and the Critic' by René Girard

- 'Literary Invention Discussion' by Charles Morazé

- 'Criticism and the Experience of Inferiority' by Georges Poulet

- 'The Two Languages of Criticism' by Eugenio Donato

- 'Structure: Human Reality and Methodological Concept' by Lucien Goldmann

- 'Language and Literature' by Tzvetan Todorov

- 'To Write: An Intransitive Verb?' by Roland Barthes

- 'Of Structure as an Inmixing of an Otherness Prerequisite to Any Subject Whatever' by Jacques Lacan

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play was presented when structuralism and its implications were not completely clear. According to Derrida, structuralism was a "frenzy of experimentation" not a movement. Instead of arriving at a clear conclusion regarding the fundamental questions of structuralism, the symposium ended up becoming a ground zero for the Structuralist controversy. The controversy was based on two significant issues that were also fundamental to Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play. The first issue was the impact and consequence of the application of the general theory of signs and language systems to all the areas of human sciences. The second issue was the mediations between the subjective and objective judgements. These became the prominent tensions in the structuralist school of thought. Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play uses the fundamental logics of structuralism to argue for a reconsideration of the concept of meaning and interpretation. He attempts to showcase an approach that accepts the absence of a fixed centrality in both meaning as well as human nature.

Major Influences- Nietzsche, Freud, Heidegger and Saussure

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play is influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Sigmund Freud and as mentioned above, by Ferdinand Saussure.

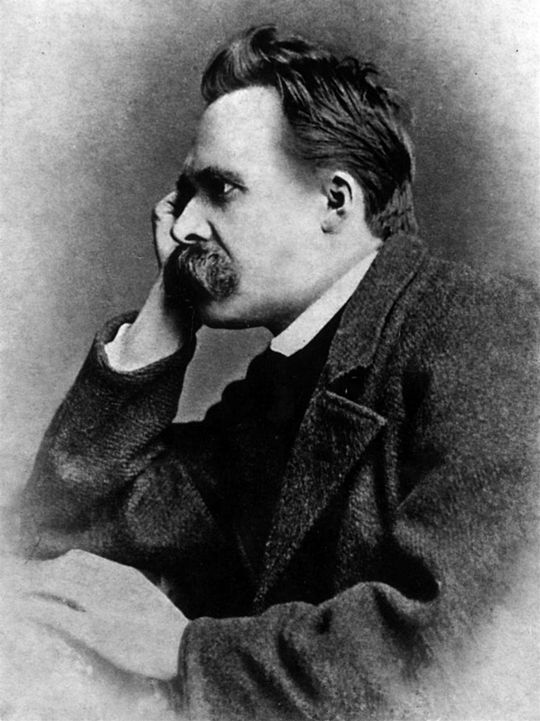

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Nietzsche was a German philosopher, popular for his ideas on existentialism. With Nietzsche, Derrida shared the doubt in philosophy and its apparently absolute truths. Just like Nietzsche, Derrida was aware how significantly we are influenced and controlled by our perceptions. Both the philosophers attempted to destabilize and reverse the binary pairs such as truth/error, moral/amoral, subject/object, etc.

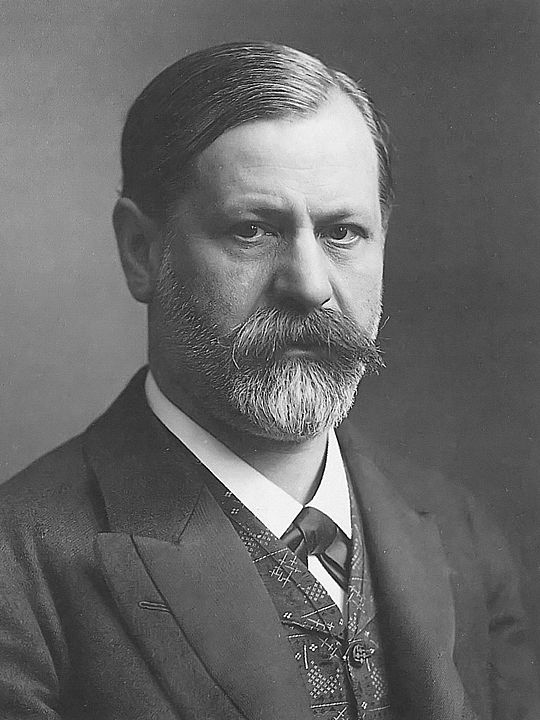

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Freud was an Austrian neurologist and was the founder of psychoanalysis. Just like Freud, Derrida questioned the unity of the human psyche as it was always haunted by the subconscious hints of our past experiences.

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

Heidegger was a German philosopher best known for his contributions in the fields of hermeneutics, existentialism, and phenomenology. The very term "deconstruction" comes from Heidegger's concept of "destruktion". Derrida also adapted Heidegger's practice of crossing out a term after writing them.

Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913)

As discussed earlier, Saussure was the founder of semiotics. He stated that just like a game of football dictates the actions of its players, our communication within a language is also governed by structure of that language. Structuralism is the core focus of Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play.

Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences

summary, explanation and analysis

In the very opening of the essay, Derrida points out that an “event” of rupture and redoubling or repetition has occurred in the history of the concept of structuralism. Derrida then proceeds to describe the history and concept of structure before this event of “rupture”.

I. History of Structure before the 'event' or the 'rupture'

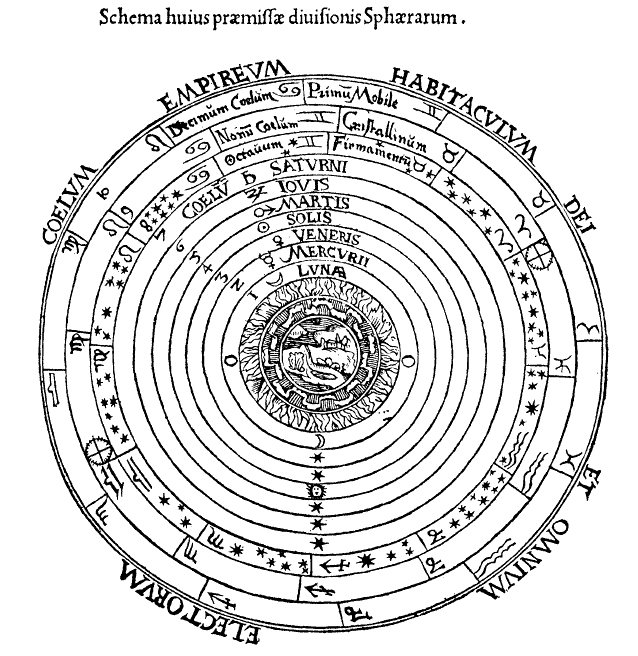

Derrida says that the concept of structure, as well as the term “structure” itself is as old as Western Science and Western Philosophy. The term ‘epistēmē’ means knowledge and understanding that is established and unquestionable. Derrida refers to the Western philosophy and science as absolutes. The term and the concept of structure is as old as epistēmē.

According to the Western philosophy, the concept of order is based on ordering of the world according to binary opposites. For example, in Genesis and Jewish scriptures, when God creates the world, he creates light by separating it from darkness, creates land by separating it from water, and creates Earth through its separation from Heaven. Therefore, we can see how order segregates the world into binary opposites.

The pre-modern world was geocentric and was ordained by God. The universe had a specific structure and order. Since it had a structure and order, it also had a center. To comprehend of a structure, an order without a center is impossible. We presume that to have a structure or an order their must be a governing center that keeps the structure coherent. Everything is a microcosm of the universe’s order that is determined by God. This way of pre modern thinking did not disappear in the modern age. Even today, we still firmly believe in centers and structures.

Derrida refers to the structurality of the structure, the centrality of the structure. Since we presume the structurality of the structure to be natural, we do not notice or talk about it, even when it is perpetually at work.

Derrida then begins to talk about the centers of the structures. According to him, structural centres dont just organize it (as per the Western philosophy and thought), they also limit free play. A structure within its set boundaries allows some extent of free play. This limitation to free play will no longer exist if there is no center in a structure. However, this will also cause an absence of coherence. Let us take an example of language. If we begin to ignore the central grammatical rules of the English language and begin to speak as and how we want, with complete free play, we will not be able to communicate coherently and effectively. Thus, a structure without any center or coherence is incomprehensible and unthinkable. Now, while a center is something that causes the existence of a structure, it escapes and stays beyond the structurality. If we think about it, there are no rules for the rules of chess. The rules exist outside the game. Thus, the center is not the part of a structure. At the center, no substitution of elements is possible. This is different from the conventional idea that the center or the origin of the structure not only holds the structure, but is also a part of it. Derrida says:

"The center is at the center of the totality, and yet, since the center does not belong to the totality (is not part of the totality), the totality has its center elsewhere".

Derrida therefore points out that the Western rationality that is based on this structure with a center is in contradiction with the episteme itself. It is "contradictorily coherent".

Derrida further states that this coherence in contradiction indicates desire. Western thinking has always desired for a center. The entire Western thought is based on the idea of an Origin, an Ideal Form, an absolute Truth, a God, etc. This center provides with all the meaning. The West has always preferred presence over absence, wholes over holes, and has always attempted to fill in the center with various substitutes. However this desire for a center simply implies that either the center does not exist, or that there is some problem with it. After all, we do not desire something that we already have, or that already exists. According to Derrida, in Structure, Sign and Play, this desired concept of a centered structure is just another play that is founded on a fundamental ground and an immovable center that is beyond the play itself. This play that is based on a structure with an absolute center is the result of and further causes the anxiety to maintain itself. This is so because in a game, certain level of anxiety is always involved, since the play is always at stake.

This anxiety ultimately leads to the freezing of the free play. A center excludes and marginalizes all other valid possibilities. For example, in a male dominant society, women will be marginalized. Similarly, a culture that has Christ at the center will marginalize any other culture that is different. This anxiety for a center leads to binary opposites such as Christian/Pagan, Spirit/Matter, Nature/Culture, etc. While the right element of the binary is privileged, the left element is marginalized. In a play that is anxious of keeping a center, our knowledge becomes dependent upon the binary codes and concepts. The dominant half of the binary regulates our reality and freeze the free play. For example, social codes, taboos, advertising, rituals, etc all attempt to dominate one element of the binary, while repressing the other. According to Derrida, language and reality are not a definite 'this and that'. They are ambiguous with several possibilities. Even if some are highlighted and preferred, there will always exist multiple possibilities.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play refers to the structural center as the origin, the end, arché (beginning), or telos. Any substitution, transformation, or even repetition of the structural center is derived from a history of meanings. This history of meanings too has a fixed origin and an end. Similarly, the field of eschatology (theology concerned with death and judgement) is also reduced to a structure with a fixed center which is beyond any play.

Derrida then begins to discuss the history of the concept of structure before the event of rupture that he mentions in the beginning of Structure, Sign and Play. Derrida looks at structures historically (diachronically), as well as at a particular juncture (synchronically). When we see a structure at a particular period of time, we cannot substitute its center. However, when one looks at the history of the concept of structure historically or diachronically, one finds a series of substitution of centers. The history of the concept of structure is simply a series of substitution of one center for another in a successive and regulated way. The center just receives different forms and names but still the center exists. These centers can be called metaphors and metonymy. For example, the period from the early Christian era to the 18th century placed God at the center. This center was then substituted by rationality in the 19th century. Rationality was eventually substituted by the unconscious, desire, and irrationality. Derrida further emphasises that one thing that is common in all these centers is "Presence" in every sense of the word. All the terms that are related to principles and fundamentals always indicate a sense of presence. Significant examples include eidos (meaning form or essence), archē (beginning), telos (aim), energeia (activity), ousia (true being), and alētheia (truth).

II. The Event or Rupture in the history of Structuralism- the absence of a center.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play further states that the event of rupture in the history of structure occurred at the moment when the structurality of the structure began to be observed, noticed and repeated. Derrida then emphasizes to think about the law that drove the desire for a stable center or origin in a structure, and the process of signification that regulates the substitutions of the law of central presence.

According to Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play, the moment we begin to examine the structurality of the structure, the moment we begin to look for the immovable, absolute center, we realise that there is none. This is similar to Saussurean linguistics where the meaning is neither intrinsic, nor positive. It is in fact differential and arbitrary (as explained in the sections above). The meaning making systems are not based upon something absolute and rational.

There is no center to a linguistic sign system, neither is there an organising principle that offers coherence to the linguistic structure. All the signs have meaning through differences. We understand day because it is not night, we understand the concept of afternoon because it is different from morning. To better understand the lack of center in linguistic sign system, we can take up the example of a dictionary. In order to find the meaning of a word, we look up a dictionary. However, the dictionary leads us to several other words, rather than the "meaning" of the word. The meaning is generated through other signs/words. Thus, we will ever arrive at a stable foundation that drives the whole system of meanings. Every word/signifier is a sound that depends on another signifier for its meaning. There just exists an endless chain of sounds. Derrida is not against the term signified but just puts it under erasure (borrowed from Heidegger). When we put a word under erasure, we cross it out. Erasure shows that the word exists but requires a closer examination. Thus, the word remains but is crossed out.

Derrida similarly points out that a center does not exist. We cannot perceive a center in the form of a 'presence', as it does not have any natural site or a function. Instead, it is a void where multiple substitutes come into play. In this moment, in this lack of a center, when everything becomes discourse. There are multiple, equally valid perspectives to see the world and each point of view has a unique language which is called discourse. It becomes a system where a transcendental signified is absent and gives opportunity for infinite play. Derrida states:

"This was the moment when language invaded the universal problematic, the moment when, in the absence of a center or origin, everything became discourse–provided we can agree on this word–that is to say, a system in which the central signified, the original or transcendental signified, is never absolutely present outside a system of differences. The absence of the transcendental signified extends the domain and the play of signification infinitely."

Derrida then introduces the concept of decentering. According to him, decentering is a way of reading, a way of interpretation that :

- Makes us aware of the existence of a binary and of a center.

- Subverts or substitutes that established center with the marginalized or repressed concept, which then becomes the new center and overthrows the traditional hierarchy

Derrida acknowledges that this new center is equally unstable, and can be as easily substituted by another center. However, this condition where multiple centers (or non-centers) become equally possible is free play. The decentering of the transcendental signified is crucial to concept of deconstruction.

III. Where and How did this decentering occur?

It was not a specific author, text that initiated the decentering. Yet, the authors in whose works decentering was the most prominent were Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Martin Heidegger.

How did Nietzsche's works facilitate decentering?

Friedrich Nietzsche was a significant German philosopher who critiqued the fundamental assumptions of conventional metaphysics that he perceived as limiting to human life. Nietzsche questioned and challenged the idea of a transcendental reality beyond the physical world. According to him, the concept of absolute truths such as God were just illusions and projections of human desires.

Nietzsche also criticized the concept of truth in his work 'The Will to Power'. He argued that truth was just a product of human perception and interpretation. Truth, for Nietzsche was always subjective and he declared that there was no truth, but only interpretations.

Nietzsche also criticized how the traditional metaphysical framework segregated the world into opposing concepts such as mind/body, good/evil, etc. He perceived this dualism as life-denying and belittling to the physical world and human instincts. Nietzsche advocated embracing human desires, instincts, uncertainty, and perspectivism. Thus, he decentered the traditional concepts of metaphysics and encouraged the concepts of play and multiple equally important interpretations.

How did Freud's work contribute to decentering?

Although Sigmund Freud did not challenge the traditional concepts of metaphysics like Nietzsche, he did challenge some conventional concepts about the nature of consciousness and self. Firstly, Freud proposed the idea of an unconscious mind that contained thoughts, memories, and repressed desires that were beyond the conscious mind. According to Freud, a significant part of human behaviour is driven by the unconscious. This questions the traditional notion that the self presence and consciousness is the complete knowledge of our thoughts and emotions.

Freud also introduced the components of the human mind- the id, ego, and the superego, that can cause internal conflicts within self. This Freudian concept of a divided self was also challenged the traditional concept of a unified and coherent self.

Heidegger's destruction of the Metaphysics

Just like Nietzsche and Freud, Martin Heidegger too challenged the established concepts and contributed to the decentering that Derrida talks about in 'Structure, Sign and Play'. Through 'destruktion' Heidegger exposed the assumptions that shaped the history of metaphysics and challenged them. He also criticised the language used in metaphysics as it consisted of abstract concepts and terminology.

These discourses by Heidegger, Freud, and Nietzsche enable us to think about the structurality of the structure. We can now view language and philosophy as unique structures with a stable, absolute center. These systems favour a center as it cements the structure as the absolute truth.

Derrida's 'Structure, Sign and Play' points out that all the decentering by the authors above is trapped in a unique circle. This circle describes the kind of relationship between the history of metaphysics and the destruction of the history of metaphysics. It is interesting to note that we rely on the very concepts of metaphysics in order to decenter it. Derrida says:

"We have no language–no syntax and no lexicon–which is foreign to this history; we can pronounce not a single destructive proposition which has not already had to slip into the form, the logic, and the implicit postulations of precisely what it seeks to contest."

For example in order to criticize language, you require to use the very same language to convey and communicate the critique. Similarly, since there is no transcendental signified and there is infinite play of signification, the very concept of sign ceases to exist. Interestingly, we still use "signs" to convey their rejection. We will always require a signifier that refers to a signified or concept. If we erase the difference between a signifier and its signified, the term signifier will have to be abandoned.

Derrida's 'Structure, Sign and Play' further refers to the preface of 'The Raw and the Cooked' by Claude Lévi-Strauss. In the preface, Lévi-Strauss attempts to go beyond the binaries of the sensible/intelligible, nature/culture, etc. Lévi-Strauss wants to go beyond the opposition between the sensory part and the intellectual part of an individual. He wants to go beyond the differential relationship between the sign system. However, Derrida claims that this impossible as one cannot operate outside of signs. Interestingly, it is the signs that enable us to think about the system of signs. Derrida says:

"The concept of the sign, in each of its aspects, has been determined by this opposition throughout the totality of its history. It has lived only on this opposition and its system. But we cannot do without the concept of the sign, for we cannot give up this metaphysical complicity without also giving up the critique we are directing against this complicity, or without the risk of erasing difference in the self-identity of a signified reducing its signifier into itself or, amounting to the same thing, simply expelling its signifier outside itself."

According to Derrida, within a sign, there will always remain a difference between the signifier or the word, and the signified or the concept. For example, the signifier or the term 'love' can be interpreted differently by different people. The signified is never absolute. The term freedom will also result in a signified or concept that will be open to interpretation.

According to Derrida, we erase the difference between the signifier and the signified in two different ways.

- The first is the classic way which gives privilege to the signified over the signifier. We consider the concept or the meaning to be stable and essential. On the other hand we perceive the signifier as just a tool or an instrument of representing the meaning or the signified. However, in doing so we overlook or ignore the complexities of the signifier itself. According to Derrida, a signifier does not represent the signified transparently, and without any play. For example, the signifier 'rose' can just mean a flower, evoke the emotions of love and romance, symbolize political movements, or even associate with thorns and pain depending upon the culture and context.

- The second way in which we attempt to erase the difference between the signifier and the signified is by questioning the system in which the first reduction of the signifier functions. In this case the signifier no longer refers to an external concept or meaning. Instead, it only refers to other signifiers instead of a signified. This process makes the meaning indefinitely deferred or delayed as the signifier continues to refer to other signifiers in an endless chain of linguistic references. When signifier and the signified collapse, it becomes difficult to arrive at a stable meaning.

- To simplify this, let us consider a sentence 'Roses are red'. In this sentence, each word is a signifier that refers to a signified or a concept. We see the words (signifier) simply representing the meaning or the signified. Thereby, the signified is privileged over the signifier.

- However, when we collapse the signifier and the signified, and actually begin to look for the meaning, all we find are signifiers. For instance, when we begin to look for the meaning of "roses" in a dictionary, we will find a bunch of signifiers instead of some stable singula meaning. The same will be the case if you attempt to find the meanings of "are", and "red". This process of endless substitutions characterizes the collapse of the signifier and the signified.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play further states that the metaphysical reduction of the sign depends upon the oppositions within a structure. Within the Western philosophy and linguistic tradition, there always exist binary relationships like speech/writing, presence/absence, mind/body, signified/signifier etc. The simplification of a sign depends upon this opposition. Derrida argues that these binary opposites are not natural but are constructed within language and thought. He also challenges the stability of these oppositions and suggests that they must be deconstructed.

This relationship between the binary opposites and the simplification of the sign is circular. Oppositions such as night/day, mind/body, presence/absence, signified/signifier are established within a language as well as thought. They create distinct categories and hierarchical divisions in our minds. This facilitates the simplification of complex phenomena by favouring one element over the other. The very process of reduction relies on the pre-existing binaries. For example, morality relies on the binary of good/bad. At the same time, the binaries of good and bad are reinforced by the simplification of the concept of morality. This is how opposition is systematic with reduction.

Derrida and Ethnology

Derrida attempts to showcase how human sciences too rely on traditional structural frameworks. He discusses ethnology as an example to illustrate deconstruction of conventional metaphysical frameworks. Ethnology is the study and comparison of different human cultures. According to Derrida, ethnology was born at the same time when the decentering of metaphysical structures had begun to take place.

According to Derrida, ethnology, just like any other structure is accompanied by discourse. Ethnology is a European science that also employs traditional concepts of structuralism even if it struggles against them. Ethnology as a human science operates within a set of pre-established concepts inherited from its intellectual and disciplinary history such as the notions of identity, rituals, social structure, etc. However, ethnologists are also aware of the biases that are inherent within the pre-existing concepts and knowledge. This makes the ethnologists struggle between the desire to describe cultures through conventional concepts and the uncomfortable recognition that these established concepts might be restrictive and inadequate.

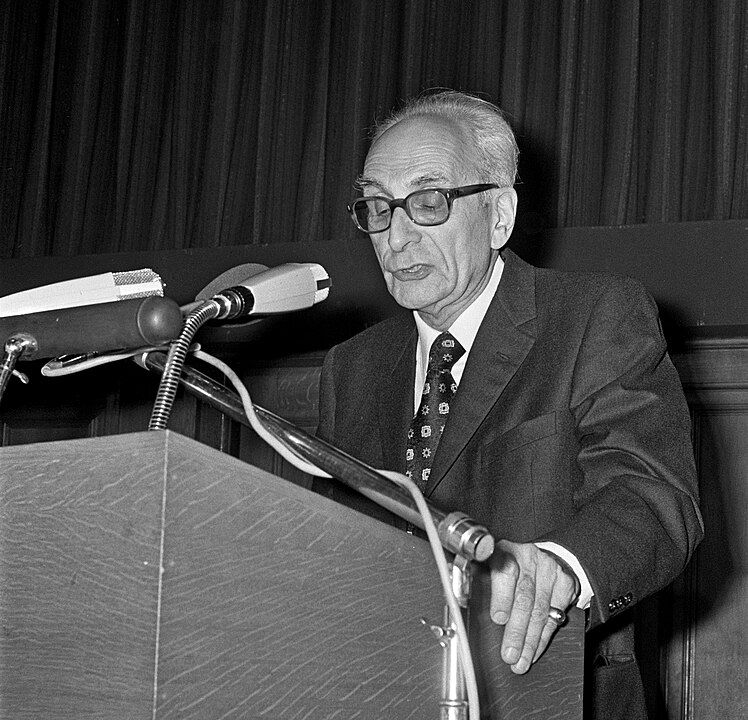

IV. Derrida's critique of Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) is recognized as the father of Structural Anthropology. Lévi-Strauss is a bridge that takes us from Saussure to Jacques Derrida. In 'Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences', Derrida refers to 'The Elementary Structures of Kinship' by Claude Lévi-Strauss. Published in 1949, Lévi-Strauss's work draws from the traditional binary pair of nature/culture. He defines nature as something universal, spontaneous and free. On the other hand, system of norms and rules that vary from one society to another belong to culture. Conventionally, nature is preferred to culture.

However, Lévi-Strauss encounters a scandal that does not comply with the nature/culture binary. The nature/culture binary simplify and reduce the human existence into either biological and instinctual or as social and constructed. Lévi-Strauss finds that incest prohibition (prohibition of sexual relations among biological relatives) is a universal phenomenon, so much so that it seems natural. At the same time, since it is a rule, it is also perceived as a cultural norm.

Derrida points out that incest prohibition operates in the realm of both nature and culture. It is rooted in the instinctive reproductive concerns about genetic diversity and is not entirely a product of societal conventions. Thus, incest prohibition cannot be categorized neatly as cultural or natural. It exists within the interplay of both the realms, thereby challenging the opposition between them. Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play deconstructs and erases the nature/culture binary and highlights their complexity. The moment we realise that incest prohibition cannot fit in the conventional nature/culture binary, and that it is beyond the opposition, it stops being a scandal. It now escapes the traditional structure.

Derrida now arrives at one of his most important statements in Structure, Sign and Play. He states that the example of incest prohibition is an example of how:

"...language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique"

This statement highlights Derrida's broader concept of deconstruction that challenges presumed hierarchies, and structures within language. Language is not a transparent medium of communication. Instead, it is a complicated system with its biases, limitations and power dynamics. Within language exist inherent contradictions, ambiguities and gaps which render the meanings unstable. Language contains the potential to reveal its own biases and limitations.

According to Derrida, the critique of language can be carried out in two ways:

- Once you observe how the opposition of nature/culture has its limits, you can begin to question the concepts systematically and thoroughly. This questioning is neither philological nor philosophical in the traditional sense of the words. This systematic questioning is instead a step outside the traditional philosophy.

- The second way in which the critique of language can be carried out is by conserving the traditional and conventional concepts while rejecting their limits. In this ways, the conventional concepts are not perceived as absolute truths. Instead, they are just seen as tools that can still be used to challenge or question established systems to which they belong. This is how the language of social science critiques itself.

According to Derrida, Claude Lévi-Strauss in 'The Elementary Structures of Kinship' preserves the traditional binary of nature/culture while questioning its truth value.

Derrida's reading of 'The Savage Mind' by Lévi-Strauss

Lévi-Strauss continues to challenge the traditional nature/culture in his 'The Savage Mind' (1962), while seeing it as a useful methodology. Now, Lévi-Strauss introduces the concept of bricolage which acts as the discourse of his method stated above.

Bricolage and Bricoleur

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play refers to Lévi-Strauss's concept of bricolage in 'The Savage Mind'. According to Lévi-Strauss, a bricoleur uses the instruments that are readily available, and that are not conventionally used for that particular function. He uses these conventional instruments through trial and error and changes them whenever needed. For instance, in 'The Elementary Structures of Kinship', Lévi-Strauss uses the traditional binary of nature/culture to expose their limitations while rejecting their truth value. According to Lévi-Strauss, societies engage in bricolage by using pre-existing cultures and norms and creating new meanings, myths, and social structures out of them. Bricolage challenges the idea that cultures or societies are developed through a linear progressive process.

Derrida refers to how according to Gerard Genette in 'Structuralisme et critique littéraire', bricolage can be applied to literary criticism.

According to Derrida in Structure, Sign and Play, every discourse is a bricoleur. Every communication and expression involves a creative rearrangement and recombination of pre-existing linguistic and cultural elements.

For instance, intertextuality. Derrida argues that all texts and speeches are connected to and influenced by pre-existing texts and speeches. Thus, each discourse is a bricolage of borrowed words, phrases, and ideas from multiple sources. No discourse can stand all alone.

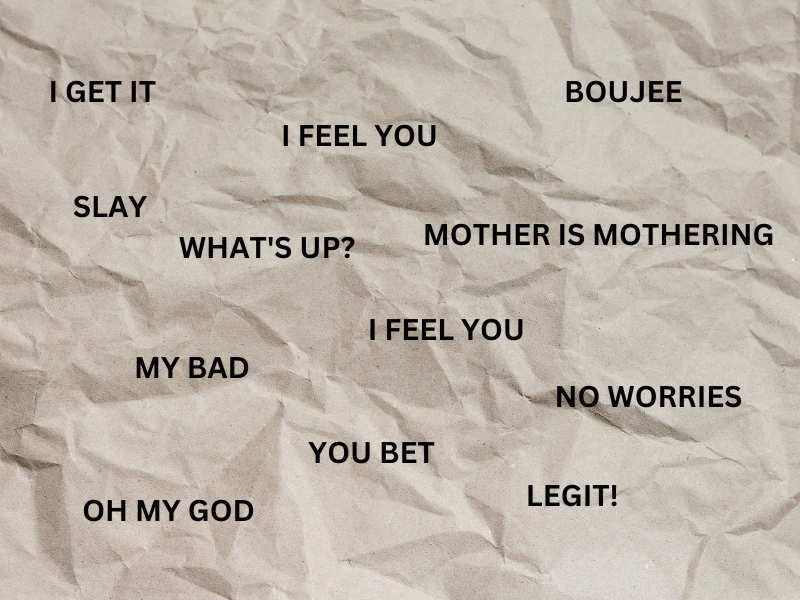

Similarly, when we use a language, we rely on existing signifiers and signifieds and rearrange them as needed. Slang is an example of bricolage in language.

Bricoleur/Engineer

Along with bricolage, Claude Lévi-Strauss also introduces the term engineer as its opposite. Bricoleur adapts the existing tools as per their requirement for unconventional uses. On the other hand, the engineer constructs his own tools and syntax. He/she is the absolute origin of the discourse as they create it out of nothing, from scratch. In this sense, engineer is a myth. Derrida critiques Lévi-Strauss's concept of engineer in Structure, Sign and Play. He states that it is impossible to have a pure discourse that is free from all historical discourses. Derrida states that since Lévi-Strauss considers bricolage as mythopoetic, the concept of engineer too is a myth made by bricoleur.

The moment we begin to question the possibility of the concept of engineer, and begin to see it as a product of bricoleur, the very binary of bricoleur/engineer is erased. Additionally, the moment we admit that every discourse is a result of bricolage, and that all scientists and engineers are bricoleurs, the meaning of bricolage as a differential concept is threatened.

Bricolage as a mythopoetic activity

According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, bricolage is not just a technical activity. It is also a mythopoetic activity or a myth-making activity. According to Derrida, the mythopoetic nature of bricolage is rediscovered in Lévi-Strauss's 'The Raw and the Cooked'. 'The Raw and the Cooked' is the first of the four-volume work on cultural anthropology titled 'Mythologiques. Throughout this work, Lévi-Strauss abandons all reference to a center, an origin, a privileged reference, or an absolute truth.

Derrida states two key points:

- The Bororo myth that Lévi-Strauss employs as the reference myth or the key myth does not qualify for having any privilege over other myths. Instead, it is just more or less a transformation of other myths in the same or neighbouring societies. Lévi-Strauss states that he could have taken any other myth as a key reference. He states that he employs the Bororo myth as the key myth not because it has some special characteristics that validate it being the reference myth. Instead, it is only because it is irregularly placed within the group of myths.

- Derrida also points out that there does not exist a stable origin of the key myth. Everything thing begins with a structure that does not have a stable, fixed center. Lévi-Strauss attempts to conduct a structured study of myths but realises that it is impossible. Therefore, he states that we must reject the traditional scientific and philosophical discourse and epistēmē that necessitates the existence of an absolute center. Thus, if the myths are founded on secondary codes, the book about myths becomes a tertiary code. The book itself becomes a myth, a myth of mythology whose absence of center is the absence of a subject and the author. It is at this point where the ethnographic bricolage assumes its mythopoetic function.

For Lévi-Strauss, a structural discourse on myths is not an epistemic discourse, it is a mythomorphic discourse, a discourse that itself resembles a myth. He states that the very act of writing or creating books about myths includes a transformative process that distorts the original myth and can create new meanings, and in turn new myths. This is what Lévi-Strauss means when he points out that 'book on myths is itself a kind of myth'.

According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, the discourse on myths is a mythopoetic function and not an empirical one. He rejects philosophic or epistemic discourses that are based on tests for proof and evidence. His mythologicals are acentric discourses that can be considered as ethnographic bricolage.

Derrida's criticism of Claude Lévi-Strauss in Structure, Sign and Play

Derrida appreciates Lévi-Strauss's exploration of the structural patterns and their absence in myths. However, at the same time he also raises several objections to his concept of bricolage and its role in mythopoetic creation. Derrida questions if we should abandon the epistemological requirements that are used to classify and distinguish various qualities of discourse.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play states:

"What I want to emphasize is simply that the passage beyond philosophy does not consists in turning the page of philosophy (which usually amounts to philosophizing badly), but in continuing to read philosophers in a certain way."

Derrida emphasizes that we must go beyond the simplifying dichotomies of accepting and rejecting. We must be open to multiple interpretations and must acknowledge the limitations and biases that are inherent in conventional philosophical discourse. Without a structure with a stable center that depicts reality, presence, and origin, without the limits enforced by that center, our experience of the world will be totalized. This means that there will be no difference between two moments or experience. We will lose all sense of organising. Therefore, Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play suggests that we should rather admit that we will always use the structures of language to emote, document, and convey experiences. However, instead of thinking of these structures as meaningless, we must see them as ones with infinite free play. That is where the actual freedom lies.

V. Concept of Totalization and Supplementarity in 'Structure Sign and Play'

According to Derrida, totalization is both at times 'useless' and at times 'impossible'. This is because we conceive the limit of totalization in two ways:

- The classical way: when there are way more things than there are forms to represent them

- The language excludes totalization because there is always something missing from it. This is from the perspective of play. The absence of the center facilitates the requirement for a continuous supplements. This supplement adds something but the absence of center still remains. Thus, the absence of a stable, absolute center is replaced by a permanent insistence of something that is missing.

What does Derrida mean by Supplementarity?

Derrida in 'Structure, Sign and Play' asserts that the totalization is meaningless not because a field is infinite and cannot be completely grasped in a glance. Instead, it is because a finite language excludes totalization. There will always be something that escapes language. The field is not infinite, but it is the substitution, the free-play that is infinite. The movement of free-play is also the movement of supplementarity that includes substitutions as well as addition. The supplementation is outside the system but is not an optional addition. In the absence of a stable and permanent center, another sign supplements it and adds to it.

Derrida points out that Claude Lévi-Strauss also uses the word 'supplementary' in his 'Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss'. According to Lévi-Strauss : "The overabundance of the signifier, its supplementary character, is thus the result of a finitude, that is to say, the result of a lack which must be supplemented." Derrida elaborates on the term and concept of supplement in his 'Of Grammatology' (1967) where he discusses the works of the French philosopher and novelist Jean Jacques Rousseau. According to Derrida, both Lévi-Strauss and Rousseau employ the term supplement to indicate something that enriches or adds. However for Jacques Derrida, the term supplement means both – something that adds or enriches, and something that makes up for something that is missing. A supplement is not just added to enrich or add, it is also assigned in a structure in place of the absent center. Thus, we can never catch the central or the absolute meaning, the meaning or the significance can never come to rest as expected from a transcendental signified.

VI. Free play in tension with history and presence

Derrida in 'Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences' states that the play is always caught up in a tension with history and presence.

Throughout Western history, metaphysics is bound with the idea of the presence of a transcendent presence, a God. Historical narratives have attempted to establish permanent meanings and interpretations of events. They have always preferred coherence, stability, truth, and closure. Play disrupts and challenges these traditional frameworks, narratives, and tendencies. According to Derrida, 'Play is the disruption of presence'. A play is always the possibilities of presence or absence. It should be conceived before you can decide about the presence or absence.

VII. The Two Interpretations of Interpretation of Structure and Sign and Free-Play

According to Derrida's Structure Sign and Play, we can interpret the interpretation of structure, sign and free-play in two ways:

- One way seeks the truth, origin and order, that is without free-play

- The second interpretation of interpretation of structure, sign and free-play is one that no longer prefers to seek an origin and acknowledges free-play. It attempts to go beyond man and humanism.

According to Derrida, both the interpretations are irreconcilable and yet share the field of human sciences. We cannot choose between them and must conceive a common ground and understand the différance of this elementary difference between the two interpretations.

VIII. Derrida's concept of Différance

Being Derrida's most popular non-concept, the term 'differance' was coined by him in his paper 1963 paper 'Cogito et histoire de la folie'. He further elaborated this concept in his essay 'Différance' that he delivered in 1968.

What does Derrida mean by Différance?

Derrida develops the term 'différance' by combining 'difference' and 'deferral'. The term and the concept of 'difference' had always been significant to Derrida as it was an important concept for thinkers who influenced him – Saussure, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Husserl. Among these thinkers, the concept of difference was most crucial for Saussure.

As discussed earlier, Ferdinand de Saussure stated that the language is based on the relationship of signs amongst each other. Words or signifiers produce meaning because they exist in a system of differences.

Example of Différance

For example: let us consider the mark "A'' . It has no meaning until it is situated between other alphabets such as "C" and "T". Thus, C A T make meaning through relationship with each other. "A" becomes itself only as an element in the system of differences. Hence, its present meaning relies upon its relationship to what it is not.

But in the case of "A", the letter is not itself until it is situated in a chain of alphabets in linear space and time. It's identity relies upon its difference from other alphabets. "A" is "A" because it is not "B", or "C", and so on. This also means that the meaning of "A" is not present in itself. It is always deferred or delayed or put off until one arrives at that space and time.

Another example of "différance" can be looking for meaning in a dictionary. If you look for the meaning of "A" in a dictionary, you will find that it is the first letter of the English alphabet. But to understand what it means, you will have to know the meaning of all the words included in the definition of "A". Hence, you never really arrive on the actual meaning of "A". It is always deferred, or postponed for later.

Thus, we never really arrive at the meaning of the concept of "différance". The term is always suspended between two meanings– to differ, and to defer. It never settles into either of the meanings. Since the meaning of différance is neither to defer nor to differ, there is not single, stable meaning that grounds it to the present and freezes its shape-shifting. The meaning will continue to dance around both the meanings.

Derrida's Structure, Sign and Play : Conclusion

Derrida concludes his seminal essay by suggesting that we must not feel at a loss regarding the absence or loss of a center. Unlike Rousseau who had become nostalgic and mournful, we must find joy and freedom in free-play and absence of an absolute presence.

Impact of Derrida's 'Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences'

Structure, Sign and Play by Derrida has often attracted criticism from several philosophical schools. The essay remains one of the watershed works in the history of literary theory and criticism. This seminal work also marks the birth of poststructuralism, even though it gained prominence in the 1970s.

Key Ideas of Derrida's Structure Sign and Play

Following are some of the most significant ideas that Structure, Sign and Play deals with:

- Bricolage: Using tools that are already available to you, unconventionally.

- Center/Origin/Truth/Presence - A center is the stable, permanent and absolute source, the existence of which is relied upon and presumed by Western metaphysics and philosophy. Derrida questions the very existence of a stable, reliable center.

- Deconstruction: Deconstruction is an interpretation where you first acknowledge the existence of a center, binary, and hierarchy within a text. It is then followed by highlighting the fault lines and gaps in the established hierarchy and then deconstructs and decenters it by briefly letting the marginalised elements take-over the center. The new center is as unstable as the conventional center. Hence, indicating at the complete absence of the presence of a center, giving way to free-play.

- Différance - Coined by Derrida, Différance simultaneously refers to both 'difference of meaning' and 'deferral of meaning'. Derrida says that because all the meaning arises from the difference between terms, we never arrive at an absolute meaning. The meaning is always being deferred or postponed.

- Epistēmē: This term is used by Derrida in 'Structure, Sign and Play' as well as by Michel Foucault. It is the dominant structure of knowledge in a particular era. The term is derived from ancient Greek and means knowledge and understanding.

- Play or Free-Play: Free-Play is when an absence of a presumed stable structure gives way to multiple possibilities and interpretations within a structure.

References

Barry, Peter. Beginning Theory : An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. 1995. 4th ed., Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017.

“Derrida, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.”” Www.youtube.com, www.youtube.com/watch?v=dlZ8fFqcT8Q&ab_channel=DougEskew. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Derrida, Jacques . “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.” The Structuralist Controversy- the Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man , edited by Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972, pp. 247–265. Accessed 24 May 2023

Powell, Jim, and Van Howell. Derrida for Beginners. Danbury, Ct, For Beginners Llc, 2007

Smith-Laing, Tim. Jacques Derrida’s Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of Human Science. Taylor & Francis, 20 May 2018.

Read More on Literary Theory

Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

About the Linguistic Sign

Langue and Parole

Strategic Essentialism