Nature of the Linguistic Sign: Saussure

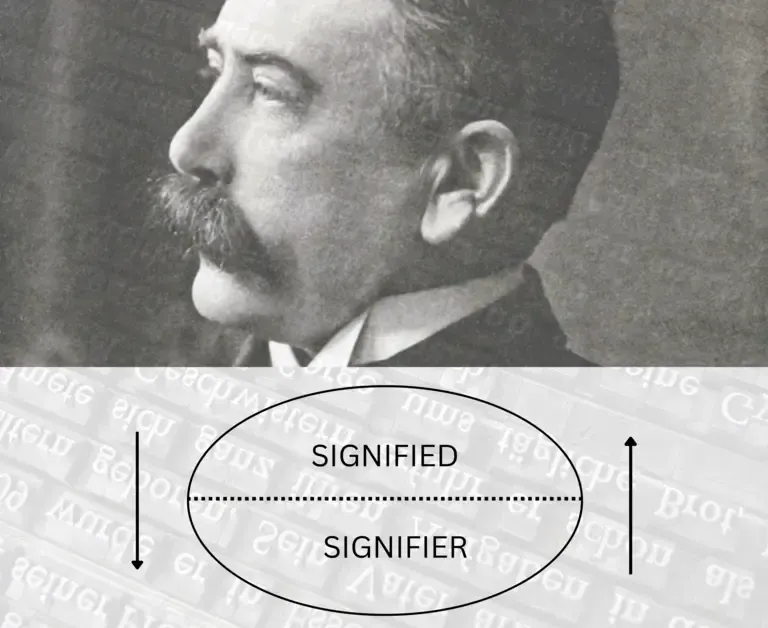

Ferdinand de Saussure explains the nature of linguistic sign clearly in Cours de linguistique générale or the Course in General Linguistics. Cours de linguistique générale was published in French in 1916 (almost three years after his death), and was a compilation of notes taken by Saussure’s students based on his lectures. It was prepared by Charles Bally and Albert Séchehaye. The book was so seminal that it was translated in seven languages between 1928 and 1983. It was translated into English in 1959 by Wade Baskin as the Course in General Linguistics. The very first part of this book by Saussure explains the nature of the linguistic sign.

What is a Linguistic Sign?

A linguistic sign can be anything that informs us something other than itself. Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics contains five parts: General Principles, Synchronic Linguistics, Diachronic Linguistics, Geographical Linguistics, and Questions of Retrospective Linguistics Conclusion. The very first chapter of the Course in General Linguistics is about Nature of the Linguistic Sign.

Prior to Saussure, language was perceived as just nomenclature, i.e. just a list of terms to label things and ideas. To Saussure, this posed three problems:

- When language is seen just as a nomenclature, we assume that the concept or idea that is labeled by the word exists independently and is not impacted by the word.

- It also does not clarify whether the term assigned to the thing is just a sequence of sounds (a vocal entity), or is a psychological entity shared by a community of speakers to communicate and interact with each other.

- It oversimplifies the link between a name and the concept, thing, or idea.

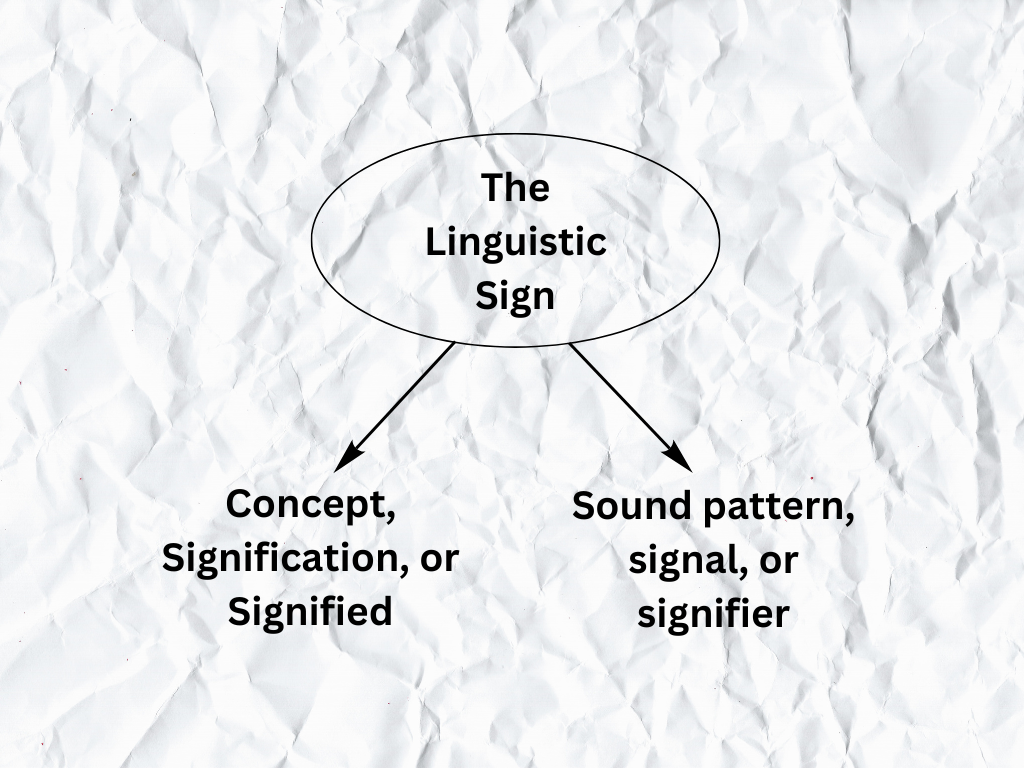

According to Ferdinand de Saussure “A linguistic sign is not a link between a thing and a name, but between a concept and a sound pattern.” We must understand that the sound pattern is not actually the sound but our psychological impression of that sound. For example, when we read the word “Elephant”, we can read the word to ourselves without making any sound and yet have a psychological impression of the sound. The sound pattern and the concept are closely linked to each other, so much so that each triggers the other. The moment you read the word “Elephant”, the image of the actual animal forms in your mind. Similarly, the moment you see an actual animal, or even a picture of one, the word “Elephant” comes to mind. Thus a sign combines both the sound pattern as well as the concept.

Thus Saussure divides the Sign into two parts. He replaces the term ‘concept’ with signification or signified, and uses the term signal or signifier for ‘sound pattern’.

Principles of Linguistic Sign

While explaining the nature of the linguistic sign, Saussure concluded that the sign has two crucial characteristics or principles:

- Linguistic sign is arbitrary

- The Signifier or the signal of the sign is linear in character

We will now try to understand both the principles governing the nature of linguistic sign.

Principle 1: The Linguistic Sign is arbitrary

The term ‘arbitrary’ means random, or without a specific reason. According to Saussure, the connection between the sign and the idea/concept/object is completely random, and has no internal connection. This principle is the main organizing principle for entire linguistics. To explain this more clearly, let us consider the object “tree”. There is no intrinsic relationship between the word “tree” (signifier) and the actual woody plant (signified).

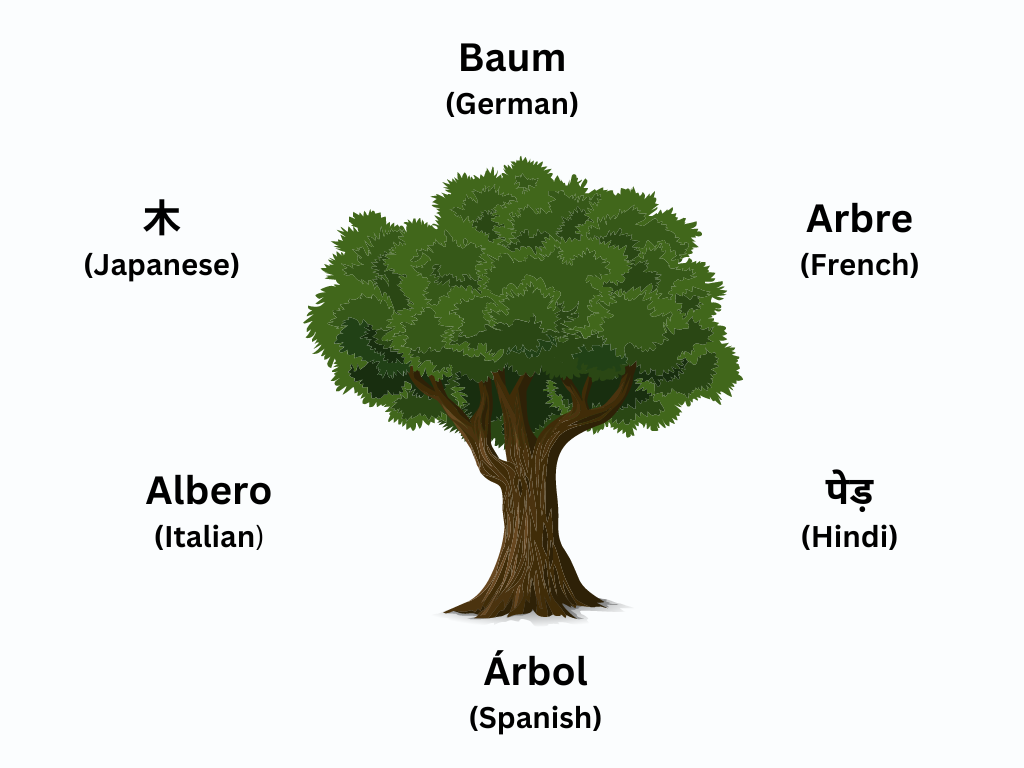

The arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign is further highlighted by the fact that one idea/concept/thing can be denoted by various signifiers in various languages. The image below illustrates this statement clearly.

As we can see in the image, the object or signified in the middle is denoted by different signifiers in different languages. This further cements Saussure’s claim that the relation between the signifier and the signified is not due to some innate quality or specific reason.

Additionally, Saussure also states that other modes of expressions such as miming are also based on the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign. For instance, the expression of joining hands out of respect in India is a sign that functions upon a convention or a collective societal habit rather than an intrinsic value of the signifier itself.

Ferdinand de Saussure further comments on the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign. He states that the linguistic sign is not arbitrary within the language. We cannot randomly change signifiers as per our wish within a linguistic community. Had this been the case, each one of us would have come up with our own signifiers and the communication would have collapsed. Saussure emphasizes that the signifier or the signal is arbitrary and unmotivated with respect to the signified concept/idea/thing.

Exception to the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign

- Onomatopoeic words, i.e, the words that are formed by the sound associated with the object they denote, are not arbitrary. For example, signifiers like hiccups, splash, boom are not arbitrary with respect to the signified object/concept. But it must be noticed that such words are very few in quantity. Additionally, some words that appear to have intrinsic relation with the signified, do so only because of the evolution of phonetics.

- We also consider exclamations as natural and spontaneous expressions. However such words too are marginal and their symbolic origin is questionable.

Principle 2: The Signifier or the signal of the sign is linear in character

To understand the second principle governing the nature of the linguistic sign, think about all written words or signifiers including mathematical equations, musical notations, etc. You will notice that a linguistic signifier or signal that is related to our sense of hearing is always linear. This is in stark contrast to the visual sign. This principle seems extremely obvious, but is as crucial as the first one. There are two kinds of signals or signifiers: auditory signals and visual signals. Visual signals such as flags, traffic lights, stop signs, exist multidimensionally. However, the auditory signifier has only one dimension, i.e. linearity of time. In the Course in General Linguistics, Saussure states that an auditory linguistic sign has the following characteristics:

“a. It occupies a certain temporal space, and

b. This space is measured in just one dimension: it is a line” (Saussure, p. 112)

Differential Relationship of linguistic signs

Let us take an example of the following sentence:

'I like roses, daisies, pansies, and daffodils'

In the sentence above we can derive meaning only through the differences among the signs. We know roses are roses because they are not daisies, pansies or daffodils. Similarly, we know what pansies are because every other flower has its own sign. Hence, we can conclude that no word can have any meaning in isolation. Meaning is only derived in relation to other signs or words. There can be no good if we have no sense of bad, there will be no happiness, if we have no concept of sadness. This concept was later used by Jacques Derrida in his 'Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences'

Nature of the Linguistic Sign: Summarized

- A linguistic sign is made of two elements: the signifier, signal, or the sound pattern, and the signified, signification, or concepts.

- There is no natural or intrinsic relationship between the signifier and the signified.

- The linguistic sign is auditory and only has one linear dimension of time.

- Meaning is derived through the differential relationship of the linguistic sign.

Understanding the nature of linguistic sign is one of the founding concepts of structuralism and its application in literary theory and criticism.

Popular (and unpopular) Questions

FAQs

Q.1 What is the nature of linguistic sign?

A linguistic sign consists of a signifier – which is the sound pattern or the signal and a signified – that is a concept that is being signaled to. Secondly, a linguistic sign is arbitrary. There is no intrinsic relationship between the signifier (the word) and the signified (concept). For example, a table is named 'table' not because of some 'table-ness' it possesses. Thirdly, the linguistic sign is auditory and linear.

Q.2 What is the linear nature of linguistic signs?

Think about any language, mathematical symbols, musical notes. Each of them makes sense only when arranged in linearity . The linear nature of linguistic sign enables us to derive meaning only when the signifiers are arranged in a linear fashion. This is in contrast with the visual objects.

Q3. What is the arbitrary nature of Sign?

According to Ferdinand de Saussure, a linguistic sign is arbitrary or random. A sign is an 'unmotivated symbol'. It has no connection between the signifier and the concept it signifies (signified). For example there is no connection between a book and the concept or the actual object called the book. This is what arbitrary nature of linguistic sign means.

References

Barry, Peter. Beginning Theory : An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. 1995. 4th ed., Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017.

De Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics. New York, Mcgraw-Hill, 1959

Read More on Theory

Langue and Parole

Structure, Sign and Play by Jacques Derrida

Toward a Feminist Poetics by Showalter

Gynocriticism

Understand Literary history

Age of Chaucer: His Life, Works & their Significance

Age of Chaucer: 1340-1400

The Anglo Norman Literature

The Anglo Norman History

Anglo Saxon Literature