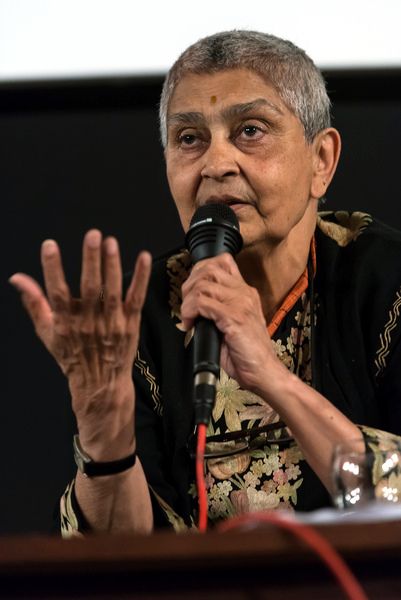

Understanding Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Key Theories and Ideas

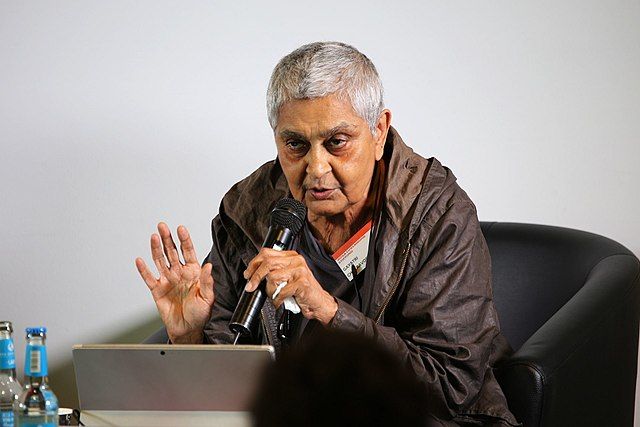

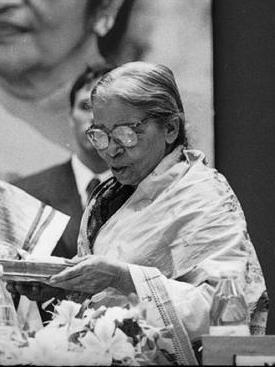

Professor Oscar Guardiola Rivera of Birkbeck College, University of London very aptly introduces Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak at the UK launch of the 40th anniversary re-translation of Jacques Derrida’s ‘Of Grammatology’

“In 1986, she started learning how to devise a pedagogical method to make the institution of democracy habitual to the children of landless, illiterate on the Western borders of Western Bengal. She trains teachers and supervisors to value intellectual labour, as she teaches the children to practice it … they have not only taught her how to read the world differently but also given her a sense of the problems of critical reading…For forty years her mission has been to expand what she calls her circle of debt.”

This blog is a beginner's handbook and includes:

- Brief Biography

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Postcolonialism

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and the Subalterns

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak - Can the Subaltern Speak?

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Deconstruction

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Feminism

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Marxism

- Why is it so hard to read Spivak?

- List of works by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Brief Biography

Early life, Education, and move to the U.S.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak was born on 24th of February 1942 in Ballygunge, Calcutta. Her parents, Pares Chandra Chakravorty and Sivani Chakravorty were simple-living, high-thinking nationalist intellectuals. They were also anti-castists and anti-communists. As a result, out of many lullabies that Spivak and her elder brother slept to, one went on roughly like this:

“all bodies are made of bone, flesh, lard, and blood, the same soul finds its dwelling there…How can you tell a Hindu from a Muslim?”

While reading Gayatri Spivak we must keep in mind that she has been familiar with conflictual coexistence and diversity since her very formative years. She was born in 1942, which was just a year before the Great Bengal Famine, and her early childhood days witnessed the Indian Independence as well as the Partition.

Schooling and graduation

Spivak completed her schooling from St. John’s Diocesan School for Girls and her intermediate from Lady Brabourne. Most of Spivak’s teachers were converted christians who had been oppressed under the Hindu caste system. They came from a section where the people were treated like animals by higher castes and were not even allowed to be near Sanskrit. Teachers like Miss Charubala Das (principal at Diocesan), Miss Nilima Pyne who taught Sanskrit (teacher-in-charge at Diocesan), and Sukumari Bhattacharji who taught English (at Lady Brabourne) are the ones who laid the foundation of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak as the academic giant who we know today.

In 1959, Spivak graduated from Presidency College as a gold medalist in both English and Bengali literature. About her days at Presidency College, Spivak tells Swapan Chakravorty–

“I feel that I was made by Presidency in a certain way. My teachers Tarak Nath Sen, Subodh Chandra Sengupta, Amal Bhattacharjee, Tarapada Mukherjee –these four I think were the ones who actually taught me how to read. Tarak-babu, in fact, the way he taught us to read, a sort of an inspired and dogged literalism – its the way I still read.”

The move to the U.S.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak recalls that she had left India because she was critical of Presidency University and had even jeopardized her first rank due to this. In 1959, Spivak borrowed $5200 and went to the U.S. to pursue her Masters’ degree at Cornell University. After completing her Masters’, she completed a fellowship at Girton College in Cambridge, England, after which she worked as an instructor at the University of Iowa. While serving as an instructor, Spivak continued her doctoral dissertation at Cornell University, on W.B. Yeats (1865-1939) titled - ‘Myself Must I Remake: The Life and Poetry’ under the literary critic Paul de Man. About working with Paul de Man Spivak recalls:

“I have lived long enough and been on enough sexual harassment cases and I’ve seen how the academy takes care of senior men. The more I look back, the more astounded I am at how impeccable he was in his attitude towards me. There weren't many foreign students in English at US universities then… I was a young good-looking person, clearly smart but nonetheless very exotic. It would have been easy for De Man not to have taken me seriously intellectually. So it wasn’t so much that he didn’t think me exotic but that he placed me in the cleanliness of intellectual recognition. I really was extremely fortunate in this.”

Intrestingly, Gayatri Spivak remembers the prevalance of harmful gendering that led her to feel that people found her to be brilliantly intellectual because she was beautiful, resulting in intellectual insecurity. Paul de Man was an exception in this case.

In the year 1977, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for the English translation of Mahasweta Devi's short stories titled 'Imaginary Maps'.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Postcolonialism

Postcolonial Thinkers: Edward Said (left) and Homi K Bhabha (right) by wikimedia commons

The majority of the Indian population consists of working-class poor people. During the struggle for Indian independence, rural peasants and women were led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and significantly contributed to the passive resistance against the British. There was significant subaltern resistance against colonial rule during the 18th century. However, their sacrifices and struggles have remained undocumented in official historic records. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak highlights and questions why nationalism has been unable to represent the majority of the Indian population -- the working-class peasants and women. She is part of the Subaltern Studies group that was initiated by Ranajit Guha (1923-2023). The Subaltern Studies attempts to re-write history that is inclusive of the experiences of subalterns who have been neglected on the basis of their ethnicity, class, gender, religion or sexual orientation.

In order to perpetuate and strengthen their dominance and for administrative convenience, the British educated upper-middle class Indians in English. This eventually created a distinct class of English educated Indians that was considered as superior to the rest of the population. The national independence movement of India, although successful in gaining freedom from British rule, maintained the class system of colonial rule. Even till today, a relatively small group of middle-class men, educated in English hold majority of political and economic power. The larger section of the Indian population still has little or no access to the benefits of Indian independence. This is persistently highlighted by Spivak.

Additionaly, Spivak states that the Western Marxist employed by the historians of the Subaltern Studies Group does not do justice to the more complicated and dense histories of subaltern resistance that they aim to recover. She challenges the notion that the Western theories of political resistance and social change are universal and all inclusive. She emphasizes that the history of India is different and complex and the Western theoretical models cannot represent it adequately. We cannot depend on them. Moreover, daily lives of Indian women are so haphazard and unsystematic that the technical vocabulary of the Western critical theory fails to represent them. This is a crisis in knowledge.

The crisis in knowledge indicates the presence of ethical risks when privileged intellectuals make political claims on behalf of the oppressed or marginalized people. This leads to the silencing of their voices and omission of their lived experiences. Additionally, it also implies that the lives and struggles of these women will only continue to be misunderstood and misrepresented with respect to the western critical theory.

While Spivak highlights the inadequacies of Western critical theories, she does not abandon them. According to the postcolonial literary critic Bart Moore Gilbert, she, along with Homi Bhabha and Edward Said, is among the first to accept and use ideas from Western critical theory in postcolonial studies. This, however is not always well received by all theorists. For instance, Aijaz Ahmad and Arif Dirlik criticise the use of western theory in the field of post-colonial studies because this inclusion indicates a new kind of intellectual colonialism complicit with global capitalism.

Introduction to Literary Theory

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and the Subalterns

If we go by the dictionary, the term ‘Subaltern’ is a junior ranking officer in the British Army. However, the intellectual source for Spivak’s meaning of Subaltern comes from Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. Gramsci used the term ‘subaltern’ to represent to unorganised groups or rural peasants. These peasants had no social or political consiciousness as a group. This made it easier for the ruling classes to lead and exploit them. Gramsci’s use and idea of the ‘subalterns’ was further developed by the Subaltern Studies Collective. The Subaltern Study Group or SSG was initiated by Ranajit Guha, and consists of South Asian scholars such as Shahid Amin, David Arnold, Partha Chatterjee, David Hardiman, and Gyanendra Pandey, who aimed to trace the histories and experiences of marginal social groups and individuals who were excluded in Indian history. According to Guha, subalterns referred to peasants who were ignored in the dominant post-independent historical narratives. It is true that India attained political freedom from the British colonial rule. However, this freedom did not correspond with the promised social revolution in the class system. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak agrees that the peasants, untouchables, and the working class have been excluded from history. However, she also points out that the Subaltern Study Group (SSG) privileges male subaltern subjects, ignoring the marginalized women. She provides a post-marxist definition of subalterns that is more flexible, informed by deconstruction, and accommodates the histories, lives, and experiences of women. Spivak’s deconstructive reading of the works of Subaltern Studies Group is criticised on the grounds of employing a western elite academic language to the history of subaltern revolutions.

There are individuals and social groups who are perpetually and historically ignored and exploited by colonialism. These people are further disempowered and misrepresented by master words like ‘the woman’, the worker’, the colonized’, used in the context of political struggles of Indian independence. One of the most significant contributions by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is her attempt to find a critical vocabulary that is appropriate to represent, and effectively describes the lived experiences and histories of misrepresented, ignored and oppressed social groups and individuals. In an interview published in Polygraph, Spivak explains:

“I like the word ‘subaltern’ for one reason. It is truly situational. ‘Subaltern’ began as a description of a certain rank in the military. The word was used under censorship by Gramsci: he called Marxism ‘monism,’ and was obliged to call the proletarian ‘subaltern.’ That word, used under duress, has been transformed into the description of everything that doesn’t fall under strict class analysis. I like that, because it has no theoretical rigor.”

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is a public intellectual for whom the overlooked exploitation and oppression of the subalterns in the postcolonial world is not only an ethical dilemma, but also a methodological challenge. In the Indian postcolonial society, political and social oppression is prevalent throughout class, religion, language, ethnicity, religion, generation, citizenship, and gender. Thus, oppression is different in different cases. Hence, the moment educated and metropolitan intellectuals begin to make theoretical claims on behalf of the subalterns, they tend to overlook significant social differences among the subaltern groups.

Additionally, in Western academia, there always exists a possibility that Spivak will be recognized as an intellectual who is speaking on behalf of the subalterns.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak strongly criticizes any attempt by privileged intellectuals to explain or claim to know the experiences of the subalterns. This strong criticism stems from her acute awareness of representative errors committed exploitatively against the disempowered groups.

The histories of the rural peasantry and the urban working class has been recorded by privileged social groups. Initially, history was documented by the British colonial administrators. Eventually, it was re-written by the educated, middle-class elite or the bourgeoisie. It is interesting to note that both the Indian English educated bourgeoisie, as well as the British administrators are the ideological products of British rule. Thus, the histories and the experiences of the marginalized working class was narrated and controlled in the interest of the ruling power or the dominant social class even after the Indian independence. The task of retrieving and re-writing the histories and experiences of the disenfranchised social groups is extremely challenging. There are no reliable historical sources or documents that narrate the experiences, lives and practices of the subaltern groups in their own terms, and from their perspectives. The subalterns have had no agency and no political voice. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, along with the other historians in the Subaltern Study Group, underlines how the histories of peasant uprisings highlight a significant gap in the historical narrative of Indian Independence.

In the early 1980s, Spivak was focused on the critique of this privileged historical documentation and representation, and saw it as a political agenda. According to her, if the political voice and agency of the subalterns could be retrieved, it could then gradually and eventually be re-written. This would also offer an effective critique of the dominant historic representation.

We must remember that Spivak’s thought about Subalterns is not in a historic or intellectual vacuum. Marxism had played a crucial role in the development of Indian political thought during the early 20th century. The works of the Subaltern Study Group employed classic Marxist methodology in their works. For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, classic Marxism was too rigid to accommodate the diverse and complex social history of India. Although Spivak critiques the methodology of the group, she does not reject Marxist thought altogether. Instead, she adapts the methodology beyond the restrictive class politics and includes liberation struggles such as peasant’s struggles, rights of indigenous minorities, and women’s movements. Spivak also criticizes the early research by the Subaltern Studies Group because of their idea that the subalterns are sovereign political subjects who are in control of their destiny. Spivak completely rejects this idea. She states that the concept of a sovereign subaltern is just a concept in the dominant discourse by the privileged. Gayatri Spivak also asserts that the notion that subalterns possess a political will is constructed by elite nationalism. The dominant bourgeoisie narratives completely neglects the individual struggles of the subalterns. For example, the Awadh peasant rebellion of 1920, the strikes by the Jute workers in Calcutta, during the 20th century, and the significant contribution of the muslim weavers of Northern Indian during the 1857 Indian mutiny.

Spivak also highlights that during the historical transition in India, from feudalism to capitalism, there was a historical account of how the bourgeoisie colonised subject transitioned into the national subject after independence. However, there is no reliable historical account of the struggles of disenfranchised groups such as peasants, women, and other indigenous social groups.

Ranajit Guha in his ‘Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency’ (1983) attempts to recover subaltern subconsciousness according to Marx’s notion of class consciousness. In this process, Guha also gives a false coherence to the subaltern groups that are much more complex and varied. This puts the Subaltern historian at risk of objectifying the subaltern and eventually controlling them through knowledge. This is how the methodology falls prey to the dominant structures of knowledge and representation. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak points out that this risk is inevitable and at the same time necessary to address the voices and histories of subalterns. Spivak recalls Derrida’s statement that ‘the enterprise of deconstruction always in a certain way falls prey to its own work’. This emphasizes how closely the practice and methodology of Subaltern Studies is associated with deconstruction.

If you are a reader seeking a clear political solution to the condition of the marginalized and oppressed groups, Spivak’s readings might frustrate you. Professor and postcolonial literary critic Niel Lazarus even points out that Spivak is not really concerned about native agency. She is instead focused on a theory about how the social practices of the oppressed are represented or not represented in privileged academic discourse.

However, Lazarus ignores that Spivak’s focus on the misrepresentation of the subalterns is just an initial step in her deconstructive reading of Indian society. She points out that contradictory to the dominant notion of India as a coherent, unified structure, the Indian society is a network of traces. Trace is a concept from deconstruction in which the meaning of a word or sign also contains concepts that it does not mean or represent. For instance, the word ‘day’ also evokes the concept of night, the word ‘woman’ might also evoke the concept of man, etc. This deconstructive vocabulary used by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak provides her with a flexible methodology to most effectively describe and accommodate the varied struggles, experiences, and histories of the disenfranchised groups like tribals, women, and peasants that are left unaccounted for in the classical Marxist methodology employed by the Subaltern Studies Group.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak demonstrates engagement with Third World subaltern women’s resistance in her dealings with literary texts. In her ‘A Literary Representation of the Subaltern’, she proposes that literary texts can be effective rhetorical sites for articulating the complex, and varied histories and narratives of subaltern women. Spivak emphasizes how fiction by Mahasweta Devi is based on 20th century Indian history. For example, Devi’s Draupadi narrates the struggles, capture, and brutal rape of a female revolutionary called Dopdi Mejhen. Dopti was captured because of her involvement in the Naxalite rebellion against the bourgeois, the landowners, and the nationalist government during the 1960s and 1970s. Gayatri Spivak’s analysis of Dropdi Mejhen (a subaltern character), is an antithesis to the erasure of women in the dominant British colonial archives, as well as in the historical documentation by the privileged middle-class nationalists. Official historic discourse has been known to focus on men as the main driving force of revolutionary politics in India. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is extremely significant because she points out that literature can provide a space to effectively demonstrate subaltern women’s revolutions in postcolonial India.

Spivak resists the desire to articulate a subaltern consciousness in a definite, pure and positive state. As discussed earlier, such a construct, although prevalent in the Marxist vocabulary, ends up objectifying the subalterns and controls them through knowledge. At the same time, Spivak does not overlook the fact that this attempt to retrieve subaltern consciousness restores causality and self-determination to them.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak - Can the Subaltern Speak?

Among the most popular, significant and equally controversial works of Spivak is her essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak’ In this seminal essay, Spivak reveals that historic conditions of political representation cannot and do not guarantee that the interests of disempowered subaltern groups will be recognized, or that their voices will be heard. This essay is extremely important because it is here that Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak further develops her own position as a postcolonial intellectual who is determined to retrieve the neglected and silenced voices in the past from the political context of the present. In ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ Spivak politically re-fomulates and alters the conventional western poststructuralist methodologies through the careful re-reading of the 19th century Indian colonial archives. The essay also marks Gayatri Spivak’s departure from the work of the Subaltern Studies Group, and her focus on the historical experiences and struggles of the subaltern women- a social group that is not only neglected by the dominant elite academia, but also by the Subaltern Studies.

Spivak asserts that the history of anti-British-colonial revolution in India excludes the involvement and contribution of women from the official historic narrative of national independence. By accommodating the experiences and struggles of disempowered women, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak expands the narrow definition of the term subaltern, initially developed by Ranajit Guha and other historians. However, since Spivak includes upper-middle class women as subalterns, she also ends up complicating the term that only represented lower-class social groups of the world. At the same time it also removes the term from class orientation. We must keep in mind that Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is not substituting class based notion with the gendered notion of subaltern. Instead, she is further expanding its scope. She highlights how complete focus on class and economics neglects the significant historical contribution of women in Indian Independence. The inclusion of women, irrespective of their class, also highlights how the term and concept of subaltern was focused on a rigid class-system as well as on patriarchal religion, family and state.

Finally, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak concludes that ‘the subaltern cannot speak’. This is because the agency and voice of the subaltern women are so entrenched in the Hindu patriarchal codes of morality and the British colonial representation of women as victims of ruthless and barbaric Hindu culture, they become impossible to recover. When Spivak says that the Subaltern cannot speak, it means that even when the subaltern attempts to speak, she is never heard. Her voice is not recognised or acknowledged in dominant political systems of representation.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Deconstruction

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) was a French philosopher born in Algeria whose theory on deconstruction had a significant impact on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Before we explore how deconstruction impacted Spivak and how she shaped and expanded the theory, let us examine the major points of the theory.

As clearly stated in his popular essay ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the discourse of the Human Sciences’, Derrida states that all meaning and coherence depends on a system of differences and binary oppositions. For example, we understand the concept of speech because it is different from writing, we understand ‘good’ because it is different from ‘bad’, and so on. Hence, in this way, all meaning is continuously deferred. Thus we never arrive at a final, stable meaning

The truth and meaning in Western philosophy is based on this omission and erasure of the concepts of différance from history.

For Spivak, Derrida is important and interesting because he attempts to challenge and dismantle the philosophical system from within. During a conversation with the theorist Oscar Guardiola Rivera, she very clearly states that the way Derrida writes is not meant for popular reading. Instead it requires some preparation on the part of the readers. She insightfully points out that the West perceives Derrida as a “dead, white, male”. Instead, we must remember that Derrida was a Jew in France who was writing from within the traditional framework of French philosophy and theory, and criticizing that very framework. For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Jacques Derrida is someone who dismantles traditional theory from within, rather than from outside, and this is significant. Finally, she declares, we will never be able to understand Derrida, if we are threatened by his history. Just like Spivak, Homi Bhabha too uses concept of différance from deconstruction in his postcolonial theory.

For postcolonial theorists like Homi Bhabha, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and Robert Young, deconstruction is specifically useful because it provides to them a theoretical vocabulary to question and challenge the very established and conventional theoretical concepts that have justified exploitation and colonization of the non-western societies. For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Derrida’s thoughts are significant to make impactful intervention in the fields of colonialism, the international division of labor between the First and the Third World, and the global economy of today.

Gayatri Spivak’s preface to ‘Of Grammatology’

One of the most important works by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in the field of deconstruction is her translation and preface to Derrida’s ‘Of Grammatology’. She translated Derrida’s work at a time when he was not as well known to the English speaking audience in the field of criticism, theory and philosophy. In her preface:

- Spivak gives a significant account of all the philosophical debates that had shaped and impacted the thought and works of Jacques Derrida.

- She also refers to critical debates questions about Derrida by Geoffrey Bennington, Simon Critchley, Rodolphe Gasché, Marian Hobson, and Christopher Norris.

- Her preface also provided insightful context about Derrida’s philosophy on deconstruction. Additionally, Spivak also offered intellectual commentaries on Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of truth, Edmund Husserl’s concept of phenomenology, Sigmund Freud’s views on memory and the unconscious, Martin Heidegger’s involvement with the question of being, and Emmanuel Levinas concepts of ethics. She also comments on Ferdinand de Saussure, Roland Barthes, Claude Lévi Strauss, Jacques Lacan, and Michel Foucault. This detailed and insightful commentary by Spivak produces a very important and scholarly introduction to the deconstructive philosophy of Derrida. Her preface goes beyond the conventional translator’s preface and instead becomes an extremely significant and must-read scholarly work on Derrida’s thought and philosophy.

The way Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak engages with Derrida’s thought and philosophy is different from the conventional way Derrida is read. Spivak also utilizes deconstructive thought beyond the Western philosophy, and in the diverse fields about women in the Third World, and postcolonial literary studies.

We must keep in mind that Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak completely refuses to attempt to represent non-western subjects. Spivak is not cynical about the possibility of political agency and the history of subaltern resistance. Instead, she is extremely aware of how the dominant systems of knowledge and representation have already damaged and misrepresented the lives of many marginalized and disenfranchised sections. She emphasizes how the western intellectuals are completely complicit in taking away the voice of the oppressed by trying to speak for them, and represent them. Deconstruction is significant and useful because it provides Gyatri Spivak a critical strategy to recognise the oppressed without damaging them. In her portrayal of Bhubaneswari Bhaduri in her seminal essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, Spivak very impactfully highlights how Derrida’s deconstruction enables and equips her to be more conscious and ethically responsible while she talks about Bhaduri’s singular, lived experience. Vocabularies of political movements have a tendency to define experiences, history, and struggle of minorities in abstract terms such as workers, women, colonized, etc. Spivak argues that such words are ‘catachresis’.

Catachresis is the misuse or abuse of a term that is used to represent (rather misrepresent) multiple and varied experiences and environments under singular signs. However, in Derrida’s concept of deconstruction, catachresis doesn't just mean misusing a word. It also means the incompleteness inherent in all the systems of meaning. For example, let us consider the term ‘tree’ in the English language. This word must represent a particular real tree, but we do not know exactly which tree does the word refer to. There exists a certain perceptual ambiguity and a crisis of meaning. At the same time the moment we think of a specific particular “tree” we also repress the possibility of any other tree. This is true for all systems of meaning.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak highlights that the vocabulary used by political movements are catachresis because they claim to represent all women, workers and proletariat. However, this becomes problematic as there does not exist a “true worker”, or “true woman” or “true proletariat”. For Gayatri Spivak, deconstruction is politically indispensable because it guards against the claims of Marxism, Western Feminism, and national liberation movements to represent and speak on the behalf of all the oppressed.

In the case of political mobilization, using master words such as anti-colonial national liberation, feminism, socialism etc is catachresis not just because they are inappropriate but also because they end up abusing the people whose lives and experiences they define. The voice of a woman or a worker is given by a political proxy, or an elected representative who speaks on behalf of constituencies. As these representatives speak on the behalf of the minorities and the oppressed, they disastrously refer to them as a unified political subject. This coherent and collective political identity is not a transparent portrait of the true worker or a woman. These identities are just a consequence of the dominant discourse that represents these groups.

By utilizing deconstruction, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak demonstrates how language of political struggle damages the workers, women, and the colonized. Through the example of Bhubaneswari Bhaduri in 'Can the Subaltern Speak?', Spivak shows how individual, complex, lived experiences, lives, struggles, and histories are erased by the unifying radical vocabulary of political discourses that is used to represent them. Deconstruction becomes important because it is a more flexible and responsible way of reading that accommodates singular lived experiences, lives, struggles and histories.

Derrida’s rethinking of Ethics and responsibility to the Other.

In the year 1980, a conference called ‘The Ends of Man’ was held in France, at the Centre Culturel International de Cerisy-La-Salle, which was eventually published in French as ‘Les fins de l’homme: à partir du travail de Jacques Derrida’ (1981). It was attended by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Jean Luc Nancy, Phillipe Lacoue Labarthe and Sarah Kofman, and they discussed how politics was situated in Derrida’s thought. This conference eventually was discussed by Spivak in her essay ‘Limits and Openings of Marx in Derrida’ published in ‘Outside in the Teaching Machine (1993)”.

In the essay, Spivak points out how the initial discussions of the conference were focused on the binary opposition between the philosophical concept of political, and politics as the real concrete event. This binary opposition was initiated by Jean-Luc Nancy and Phillipe Lacoue Labarthe. However, Spivak in her essay states that this binary of politics as an abstract philosophical concept and politics as real event is problematic. This is because this segregation reduces and restraints deconstruction as just an abstract philosophical practice that is disconnected from the actual political events. Spivak avoids this and rather focuses on careful readings of Derrida’s early and later works. She asserts that in his works there is a movement from philosophical questions about being (ontology), knowing (epistemology) and truth, towards the ethical and social aspects of violence, justice, friendship, and hospitality. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak emphasizes that deconstruction of the conventional Western philosophy has an ethical aspect to it that questions all rational programmes that make up political decision making.

Derrida and Ethics

Derrida’s concept of ethics is based on the thoughts of Emmanuel Levinas stated in his work ‘Totality and Infinity’. According to Levinas, “ethics is nothing more than the singular event in which the Self encounters itself in an ethical relation to the face of the Other.” It is the moment the Self comes face to face with the Other, when the question of ethics is initiated. Derrida did not completely dismiss Levinas’s philosophy. Instead he emphasized how there was absolutely no guarantee that the singular event of face to face encounter between the Self and the Other will be ethical. He states that there is nothing to prevent the Self to harm or even kill the Other. Simon Critchley in his ‘The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas’ states that the “attempt to articulate conceptually an experience that has been forgotten or exiled from philosophy can only be stated within philosophical conceptuality, which entails that the experience succumbs to and is destroyed by philosophy’. The moment we attempt to ethically and responsibly respond to the Other, we risk destroying their voice. At the same time, this attempt to responsibly acknowledge and interact with the Other might also transform the Self-centered philosophical discourse such that it begins to recognise the Otherness. Deconstruction takes this chance. It questions the principal conditions of possibility that make western philosophy and theory comprehensible, and attempts to trace the ‘Other’ people, experiences, histories, or cultures that are excluded, destroyed or silenced.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak employs Derrida’s method of reading with literary and historical discourses in order to trace the omissions that are inherent in Marxism, decolonisation and feminism. For Spivak, the greatest gift of Deconstruction was that it emphasizes and recognizes the complicity of theory with the object of its critique.

In her ‘A Literary Representation of the Subaltern’ (1988), Spivak challenges the socialist and democratic false promises made to people by the representatives and leaders of the anti-colonial resistance movement during India’s struggle for freedom. She states that these promises completely ignore and omit the lower-caste workers and women. These people find no place in the new Independent India. According to Spivak, the mythology of 'Mother India' that was concocted during and after India’s struggle for freedom only perpetuated the class system that was established during the British rule. Indian Independence did little to nothing for lower-castes, subaltern women. She challenges this class-based structure of nationalist mythology in her analysis of ‘Breast Giver’, a short story by Mahasweta Devi. Through the deconstructive reading, Gayatri Spivak emphasizes how decolonisation ends up perpetuating the colonial structures of class and gender that it claims to oppose and get rid of.

‘Imperialism and Sexual Difference’ is another essay where Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak uses deconstructive approach to assess political programmes. In the essay, she highlights how western feminism and feminists are unable to incorporate the experiences of Third World women, during the construction of the universal feminist subject. All women throughout the world do not suffer the same kind of oppression. Moreover, the western feminist criticism focuses entirely on how women are excluded from the ‘masculinist truth-claim to universality or academic objectivity’. As a result, this focus perpetuates the universalist errors by suggesting that all women tolerate the same oppression just because they are women. Spivak critiques Western feminism for ignoring the experiences of Arab, African, and Asian women through the lie of ‘global sisterhood’. This critique of feminism clearly illustrates the importance of the practice of deconstructive reading. Deconstruction underlines how almost all intellectual practices are politically complicit and involved with political and social structures.

Spivak’s deconstructive reading is often criticized on the grounds that it leads to nothing more than a critical paralysis rather than amount to any effective political intervention. For example, Asha Varadharajan states that Spivak’s exposure of complicity ends up preventing her from articulating the specific moments of political resistance. However, for Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the deconstructive acknowledgement and affirmation of complicity does not paralyze critical or political thinking. Instead, it becomes the starting point from where we can develop a more responsible and aware intellectual practice.

Spivak employs deconstruction beyond its narrow disciplinary framework and engages it with political concerns. For example, in ‘Responsibility’ (1994) published in Boundary, she interrupts Derrida’s analysis of Heideggar’s philosophy and discusses political issues such as the limitations of the World Bank’s 1993 Flood Action Plan in Bangladesh. Similarly, in ‘The Setting to Work of Deconstruction’ (1999), she interrupts a summary of Derrida’s thoughts to analyze counter-globalist development activism.

In this way, works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak deviate from the conventional disciplinary codes of western critical theory. She attempts to rework the ethical dimensions of critical theory and assumptions that shape political practices.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Feminism

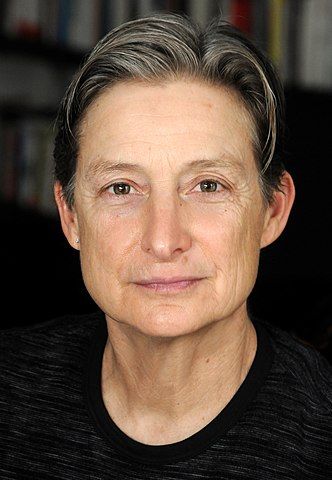

Hélène Cixous by Claude Truong-Ngoc (left) Judith Butler (right)

Spivak’s works like ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, ‘The Rani of Sirmur’, and her commentaries on the works of Mahasweta Devi, have significantly impacted the Western feminist thought. One of Spivak’s most significant contribution is the demand that Western feminism must accomodate and acknowledge the material histories, experiences, and lives of the ‘Third World’ women in its narrative of women’s struggles against oppression.

Spivak also wrote about French feminist theory, 19th century English women’s writing, and Marxist feminism. In her works like ‘French Feminism in an International Frame’ (1981), ‘Feminism and Critical Theory’ (1986), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak provides us with insightful commentaries on French feminist thinkers like Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, and Hélène Cixous.

One of the main contributions of Spivak in feminism is that she challenges the universal, dominant, and conventional assumptions of feminism that they speak for all women. She collaborated with prominent postcolonial feminist thinkers such as Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, Nawal El Saadawi, and Kumari Jayawardena and emphasised that feminism must respect and recognise different races, religions, class, cultures, and citizenship among women. We must be mindful that Spivak is not an anti-feminist. Instead, she rigorously attempts through her critique, to strengthen the arguments and political claims of feminist thought.

The early feminist social and political struggles during and after the 1950s had successfully facilitated democratic rights and freedoms of women in North America and Europe. This feminist struggle was based on liberal humanism according to which all humans were equal and must have equal rights. At the same time, European feminist Simone de Beauvoir pointed out that liberal humanism traditionally perceived women as ‘other’ or as ‘inferioir’ to Man who was the universal humanis subject.

The difference between men and women was based on biological foundation that was absolute and unaffected by social or cultural influence. However, Beauvior rejected this universal humanist notion. She asserted in her seminal work ‘The Second Sex’ that ‘one is not born a woman, one becomes a woman’. She asserts that gender identity is always informed by social construct and can be resisted through political as well as social resistance and struggle. French feminist thinkers like Judith Butler, Luce Irigaray, and Julia Kristeva concur with Beauvoir that gender identity is socially constructed. However, at the same time, it is not something that can be ignored or avoided at will. This is because gender identity is entrenched and regularly enforced by powerful patriarchal institutions like Family, Education, Media, Law and the State.

For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Luce Irigaray and Julia Kristeva have been extremely influential in redefining the Western feminist thought. Spivak suggests in ‘This Sex Which is Not One’ , that the attempt to independently define a woman risks ‘falling prey to the very binary oppositions that perpetuate women’s subordination in culture and society’. Against this binary system of men and women, she proposes a critical strategy called strategic essentialism.

Spivak’s contibution to feminism is immensely influenced by Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous. However, she shifts the focus of feminist concern about the difference between men and women to the cultural differences between the women of the First World and those in the First World.

One of the main loopholes of French Feminism is that it tends to narrate the experiences of Third World women in terms of west female subject. This approach overlooks major crucial differences in culture, language, history, and social class. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak further develops this idea in her analysis of Mahasweta Devi’s short story ‘Breast Giver’. In the story, Jashodha, a subaltern female protagonist, works as a professional mother and wet nurse for an upper-class Brahmin inorder to support her crippled husband. Spivak highlights how the Jashodha challenges the conventional western feminist assumption that childbirth is unwaged domestic labour. Her reproductive body and breast milk are a valuable asset and a source of income for her and her crippled husband. Unfortunately, the continuous exploitation of Jashodha’s reproductive body results in her painful death from breast cancer. Through her analysis of this short story, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak points out how Western Marxist feminism neglects and underplays the theory of value and ignores the mother as a subject. This is how Jashodha challenges the universal assumption of western feminism to speak on behalf of all women.

The struggles and lives of subaltern women like Jashodha are far removed from the experiences and practices of feminism in a university classroom. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak points out that this privileged distance from the Third World women must not cause us to forget the perpetual oppression suffered by them. She asserts that careful reading, specially in a university classroom has potential political and social consequences.

Gayatri Spivak also points out how the world portrayed in literature, history, and media motivate people to ignore and forget about the struggles, lives, and experiences of subaltern social groups. She challenges this academic and popular ignorance towards Third World women through her project of ‘un-learning our privilege as our loss’. This project of un-learning has been impactful on feminist theory and criticism.

Read More on Feminism

To understand misrepresentation of Third World women let us take the example of the 2001 film Kandahar by Mohsen Makhmalbaf. In this movie, Makhmalbaf portrays the wearing of burka as an indisputable sign of women’s subjugation and oppression. The issue with such an absolute assumption is that it reinforces the stereotypical image of the Third World woman as a passive victim. It indicates that all women wearing a burka are oppressed. This is not true and is effectively demonstrated by professor Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses’, by Frantz Fanon’s ‘A Dying Colonialism’, and Gillo Pontecorvo’s movie ‘The Battle of Algiers’. These works show how women have actively participated in anti-colonial revolutions and are not simply passive victims. Moreover, the wearing of a burka is not universally an act of subjugation but also a tool to conceal weapons.

In her essay ‘French Feminism in an International Frame’, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak tracks down the tendency of western feminism to represent the experiences of Chinese women in terms of western female subject, in the works of Julia Kristeva. She highlights how Kristeva’s book ‘About Chinese Women’, focuses more on how her identity as a western woman is questioned when she comes face to face with the silent women of Huxian, a village 40kms away from Xi’an. It might initially seem that Kriteva is trying to engage and learn from the experiences of the villagers, but ultimately the focus stays on the western woman. Kristeva questions - ‘Who is speaking, then, before the stare of the peasants at Huxian?’. For Spivak, such a question only demonstrates the narcissistic tendency of western intellectuals to address other cultures only as a way to challenge the authority of the western subjectivity. The questions still remain self-centered. This makes Spivak question if Kristeva’s model would be able to benefit Chinese women at all. According to her, additional questions must be asked such as -- Who is the Other woman? , How am I naming her? and how does she name me?

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak also points out that Kristeva’s revolutionary characterization of women’s sexual desire completely neglects significant cultural and class differences among women. In her ‘French Feminism in an International Frame’ she challenges the dominant Eurocentric assumption that clitoridectomy is a ritual exclusively imposed on women from Third World, remote and primitive societies. Spivak points out that symbolic clitoridectomy or suppression of female sexuality has been prevalent among all women and has been a general condition of female economic and social oppression.

In her essay ‘Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism’, published in the U.S. journal Critical Inquiry, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak focuses on 19th century British fiction. In the essay she analyses three texts: Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Jane Eyre’, Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, and Jean Rhys’s ‘Wide Sargasso Sea’.

In her analysis of Jane Eyre, Spivak highlights how the narrative of the novel completely focuses on Jane Eyre. The novel completely ignores the historical significance of Bertha Mason, a white Jamaican Creole woman who is the ‘mad’ first wife of Rochester. In the novel, Bertha Mason is just some ‘Other’ who is not even a human. For Spivak, this characterization of Bertha Mason is strikingly similar to Julia Kristeva’s description of the ‘unknowable stare’ of the peasants in her ‘About Chinese Women’. In both cases the women are stripped off any cultural or historical identitiy. They just become an Oriental Other who reflect the stability of the western female. In this way, for Spivak, both Kristeva’s ‘About Chinese Women’ and Brontë’s ‘Jane Eyre’ simply reproduce the stereotypes of colonial discourse in the representation of western female individualism. Spivak points out that the individual rights and freedom that are given to Brontë’s protagonist Jane Eyre are denied to Bertha Mason. She locates basic gender inequalities between Jane and Bertha. Bertha Mason is deprived of the category of a female individual because she is a Jamaican Creole. The othering of the non-western woman results in the justification of British imperialism as a social mission. It portrays British cultural values superior than those of colonial world.

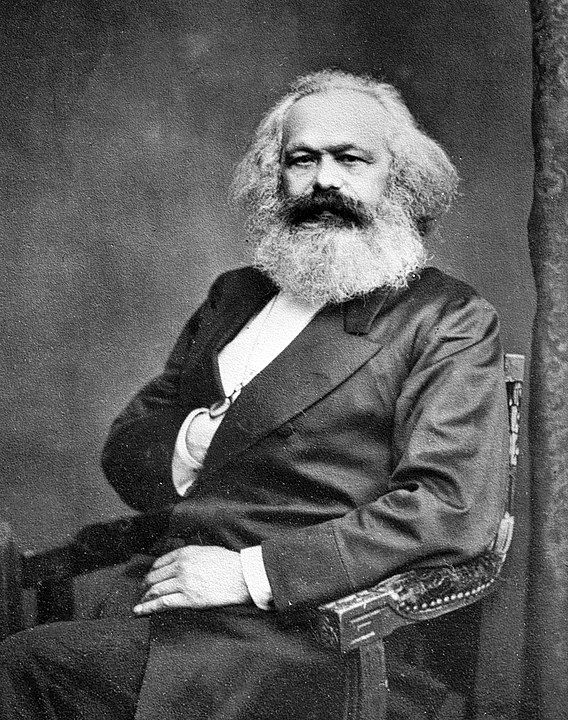

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Marxism

The pivotal idea proposed by Marxism is that every area of social life including politics, religion, education, media, arts, as well as culture are determined and shaped by economic relations. Marxsim analyses the real, material conditions of everyday life. It does not focus on abstract ideals like truth, spirit, beauty, or consciousness. Karl Marx states in ‘Preface to A Critique of Political Economy’ that “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness". Today, the writings of Karl Marx are often considered obsolete with respect to the current social and economic life of the western world.

However, intellectuals like Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Samir Amin, David Harvey, and Ernesto Laclau find it important to revisit and re-read Marxism in today’s time. Karl Marx in his writings had completely ignored India and Africa. As a consequence of this ommision, many critical thinkers like Edward Said criticized Marx for his Eurocentric model of social change. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is also aware of Eurocentricism in Marx’s thoughts. In her ‘A Critique of Postcolonial Reason’, Spivak condemns Marx’s writings on India for attempting to include a non-Europe into a ‘Eurocentric normative narrative’. However, she does not completely reject the theory and writings of Karl Marx.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak approaches Marxism through Derrida’s deconstructive philosophy. She does this to safeguard against the impatient interpretations of Marx’s work that move from reading and interpretation to the demand for political and social change way too quickly. Moreover, Gayatri Spivak challenges Marx’s early ideas on both philosophical as well as ethical grounds. On philosophical grounds, Spivak questions Marx’s humanist idea that the struggle of the working-class for economic equality represents political interest of all humanity, irrespective of place or time. On ethical grounds, she challenges Marx’s claim made on behalf of the European working class, that completely overlooks other disenfranchised social groups like women, the colonised, and the subalterns. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak focuses on Marx's later writings such as ‘Grundrisse’ and ‘Capital’. Her re-working of Marxist thought is a response to the changing gendered as well as geographical dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

Much of Marx’s later writings were informed by the economic conditions of the European working class men, even when he was aware about colonialism in India and Africa. He was also aware of the unwaged domestic labour among women. Yet, Marx prioritized the experiences of male European workers during 19th century industrial capitalism. For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the conditions for contemporary economic exploitation are different. Today, multinational corporations sub-contract production and manufacturing to places where the workers are not unionised and are therefore more vulnerable to economic exploitation. In her ‘Feminism and Criticial Theory’ Spivak points out how global capitalism functions by employing vulnerable working-class women who lack any representation, union, or protection against economic exploitation. Because the conditions of the contemporary capitalism are geographically dispersed, it is extremely difficult for the Third World female workers to organise and represent themselves in a conventional political and philosophical ways. This is different from the European working class men in the 19th century, who were able to from unions and eventually were able to demand for better working conditions, pay, etc.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak also highlights how modern transnational capitalism also exploits women’s productive bodies. This makes it absolutely necessary to re-read and re-think marxism that deviates from the conventional androcentric European definition of the working class and accommodates the exploitation of disenfranchised working women in the Third World

Why is it so hard to read Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak?

Edward Said (1935-2003) in ‘The World, the Text, the Critic’ has criticized obscurity in literary theory. He states that because the terms and texts of literary theory are difficult to comprehend and access, they become distanced from real social life. They only encourage academic scholarship that is far removed from social realities. Spivak is notorious for being dense and complex in her writings. Going by Said’s attack on the obscurity in theoretical texts, we might blame Spivak for her complex texts. Just like Edward Said, British Marxist critic Terry Eagleton also criticizes Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s writing style in his article titled ‘In the Gaudy Supermarket’, published in the London Review of Books in 1999. However, Spivak’s complexity does not serve some ornamental academic fashion. Instead, it is a conscious decision on her part.

Spivak critically engages with the most complex and difficult European philosophical discourses by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), Hegel (1770-1831), Marx (1818-1883), Freud (1856-1939), Derrida (1930-2004), and Foucault (1926-1984). Jacques Derrida’s work on writing and textuality had a great impact on Spivak. Just like him, she questions the conventional, stable notion that language transparently reflects and constitutes the world. In an interview with Elizabeth Grosz, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak points out that this perception that language transparently represents the world is bound with the history of European imperialism. Thus, the writing style of Spivak indicates political commitment to highlight oppression and exploitation under global capitalism. She resists writing simple, clear prose because she wants the implied reader to interrogate about how they interpret literary, economical, and social texts in the aftermath of colonialism. According to her, the way one presents theoretical ideas must reveal the contradictory nature of social and geopolitical relations rather than concealing them.

It is hard to understand Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak because her complex style of writing is inseparable from her theoretical method. Although Spivak is famous for dealing with Feminism, Marxism, Deconstruction, and Post-colonialism, she does not completely adhere to any of the theories, and frequently highlights their limitations. After all, all the theoretical models are deeply influenced by colonial influence. In an interview with Elizabeth Grosz, Spivak argues that ‘the irreducible but impossible task is to preserve the discontinuities within the discourses of feminism, Marxism and deconstruction.’ She labels this task as the ‘critical interruption’ of deconstruction, feminism, and Marxism. We can understand Critical interruption better if we place it in Third World political thoughts. Spivak’s critical interception is clearly evident if we begin to compare her theoretical arguments in critical essays written by her:

She highlights the importance of Marx’s labor theory of value while thinking about international division of labor between the Third and the First World in ‘Scattered Speculations on the Question of Value’. However at the same time in ‘A Literary Representation of the Subaltern (1988), and ‘Feminism and Critical Theory’ (1978), she criticizes the same labor theory of value because it omitted the unwaged productive as well as reproductive labor of Women in the Third World.

In ‘French Feminism in an International Frame’ (1981) and ‘Imperialism and Sexual Difference’, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak blames western feminism for neglecting the condition and issues of Third World women.

Spivak emphasizes that deconstruction as a critical theory is a safeguard against the optimistic promises that theories like feminism and Marxism make to the oppressed in the Third World. However, at the same time she also challenges and questions political claims on behalf of western poststructuralism. In the very opening of her seminal essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ Spivak refers to the conversation between Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault titled ‘Intellectuals and Power’. She criticizes how both Deleuze and Foucault completely ignore the international labor division that is prevalent between the First and the Third World. Similarly, in ‘Ghostwriting’ (1995) Spivak also states that Derrida misunderstands Marx’s main argument about capitalism in ‘Capital Volume Two’ because of which he is not able to comprehend the systematic character of emerging global capitalism.

Thus, since Spivak never completely or straightaway agrees with any critical theory, and often performs critical interruptions of Marxism, feminism and deconstruction, it becomes harder to understand her. She is difficult because she does not attempt to diminish or reconcile the discontinuities in Marxism, feminism and deconstruction. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak refuses to reconcile these gaps and discontinuities in these popular critical theories because she aims to rethink them with respect to the oppressed and subaltern groups of the Third World. She is divided between political commitment and theoretical rigor. Spivak is not just a critical commentator on significant European philosophers like Derrida and Marx. She asserts the urgent importance of mindful reading in the contemporary environment of political urgency. She goes beyond the established western philosophy and theory and attempts to mold them with respect to the whole world, specially the Third World. Robert Young in ‘White Mythologies’ (1990) argues:

“Instead of staking out a single recognisable position, gradually refined and developed over the years, [Spivak] has produced a series of essays that move restlessly across the spectrum of contemporary theoretical and political concerns, rejecting none of them according to the protocols of an oppositional mode, but rather questioning, reworking and reinflecting them in a particularly productive and disturbing way.” (Young 1990: 157)

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is tough to read because:

- She does not believe that simple, direct language transparently represents the world. According to her ‘plain prose cheats’. For Spivak, simple language cannot capture and represent the oppressed. Simple language is known to be a tool to control and dominate people.

- She refuses to ignore the limitations and gaps in the popular Western theories of Marxism, feminism, and deconstruction. She does not completely adhere to any one critical thought and keeps reworking the existing Eurocentric theories in context of the oppressed of the Third World. This makes her work harder to understand.

- Her complex writing style is a political commitment to describe how the Third World is still oppressed and exploited by global capitalism.

- Spivak writes the way she does because she wants us to pause and reflect how we make sense of texts in the aftermath of colonization.

List of works by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Books, Essays, Articles

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has produced a plethora of seminal essays and books in the fields of Deconstruction, Marxism, Feminism, and Postcolonialism. Below is the comprehensive list of works by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

List of Books by Gayatri Spivak

Below is the list of Books written by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

- 1974- Myself Must I Remake: The Life and Poetry of W.B. Yeats

- 1976- Of Grammatology (translation in English with a critical introduction to De la grammatologie by Jacques Derrida)

- 1987- In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics

- 1988- Selected Subaltern Studies

- 1990- The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues

- 1993- Thinking Academic Freedom in Gendered Post-Coloniality

- 1993- Outside in the Teaching Machine

- 1994- Imaginary Maps

- 1995- The Spivak Reader

- 1997- Breast Stories (translation and a critical introduction to three stories by Mahasweta Devi)

- 1999- Old Women (translation and a critical introduction to three stories by Mahasweta Devi)

- 1999- A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Towards a History of the Vanishing Present

- 2000- Song for Kali: A Cycle (translation with a critical introduction of Ramproshad Sen)

- 2002- Chotti Munda and His Arrow (translation and a critical introduction to a novel by Mahasweta Devi)

- 2003- Death of a Discipline

- 2006- What is Gender? Where is Europe? Walking With Balibar

- 2006- Conversations with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

- 2007- Who Sings the Nation State?

- 2008- Other Asias

- 2010- Nationalism and the Imagination

- 2012- An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization

List of Essays/Interviews/Articles by Spivak

- 1965- ‘Shakespeare in Yeats’s Last Poems’ in Shakespeare Memorial Volume

- 1968- ‘Principles of the Mind: Continuity in Yeats’s Poetry’

- 1970- ‘Versions of a Colossus’ in Journal of South Asian Literature

- 1971- ‘Allégorie et historie de la poésie: hypothèse de travail’

- 1972- ‘A Stylistic Contrast Between Yeats and Mallarmé’ in Language and Style

- 1972- ‘Thoughts on the Principle of Allegory’ in Genre (p. 327-352)

- 1973- ‘Indo-Anglian Curiosities’ in Novel (p. 91-93)

- 1973- ‘A Look to the Future’ in the Grinnell Magazine (p. 15-16)

- 1974- ‘Decadent Style’ in Language and Style (p. 227-234)

- 1975- ‘Some Theoretical Aspects of Yeats’s Prose’ in Journal of Modern Literature (p. 667-691)

- 1977- ‘Glas-Piece: A Compte-Rendu’ in Diacritics

- 1977- ‘The Letter as Cutting Edge’ in Yale French Studies

- 1978- ‘Anarchism Revisited: A New Philosophy’ in Diacritics

- 1978- ‘Feminism and Critical Theory’ in Women’s Studies International Quarterly (p. 241-246)

- 1979- ‘Explanation and Culture:Marginalia’ in Humanities in Society

- 1979-80- ‘Three Feminist Readings: McCullers, Drabble, Habermas’ in Union Seminary Quarterly Review

- 1979-80- ‘Review Essay on Robert R. Magiola, Phenomenology and Literature: An Introduction’ in Modern Fiction Studies

- 1980- ‘A Dialogue on the Production of Literary Journals, the Division of the Disciplines and Ideology Critique with Professors Gayatri Spivak, Bill Galston, and Michael Ryan’ in Analecta

- 1980- ‘Unmaking and Making in To the Lighthouse’ in Women and Language in Literature and Society

- 1980- ‘Revolutions That As Yet Have No Model: Derrida’s Limited Inc.’ in Diacritics

- 1980- ‘Finding Feminist Readings: Dante-Yeats’ in Social Text

- 1981- ‘Il faut s’y prendre en s’en prenant à elles’ in Les Fins de l’homme’

- 1981- ‘Sex and History in the Prelude (1805), Books Nine to Thirteen’ in Texas Studies in Literature and Language

- 1981- ‘Reading the World: Literary Studies in the 80’s’ in College English (p 671-679)

- 1981- ‘French Feminism in an International Fame’ in Yale French Studies

- 1981- “‘Draupadi’ in Mahasweta Devi” in Critical Inquiry

- 1982- ‘The Politics of Interpretations’ in Critical Inquiry

- 1983- Review Essay on Beatrice Fansworth, On Aleksandra Kollontai in Minnesota Review

- 1983- ‘Some Thoughts on Evaluation’ in CLAM Chowder

- 1983- ‘Displacement and the Discourse of Woman’ in Displacement: Derrida and After

- 1983- ‘Marx After Derrida’ in Philosophical Approaches to Literature: New Essays on Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Texts

- 1984- ‘A Response to John O’Neill’ in Hermeneutics: Questions and Prospects

- 1984- ‘Description and Its Vicissitudes’ in Description, Sign, Self, Desire: Critical Theory in the Wake of Semiotics, Semiotica

- 1984- ‘Love Me, Love My Ombre, Elle’ in Diacritics

- 1984-85- ‘Criticism, Feminism and the Institution’ in Thesis Eleven

- 1985- ‘Strategies of Vigilance’ in Block 10

- 1985- ‘Can the Subaltern Speak? Speculations on Widow Sacrifice’ in Wedge

- 1985- ‘Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism’ in Critical Inquiry

- 1985- ‘The Rani of Sirmur: An Essay in Reading the Archives’ in History and Theory

- 1985- ‘Feminism and Critical Theory’ for Alma Mater: Theory and Practice in Feminist Scholarship

- 1985- ‘Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography’ in Subaltern Studies IV: Writings on South Asian History and Society

- 1985- ‘Scattered Speculations on the Question of Value’ in Diacritics

- 1986- ‘Literature, Theory and Commitment: III’ in Crisscrossing Boundaries in African Literatures.

- 1986- ‘Imperialism and Sexual Difference’ in Oxford Literary Review

- 1987- ‘Speculations on Reading Marx: After Reading Derrida in Post-Structuralism and the Question of History

- 1988- ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture

- 1988- ‘Practical Politics of the Open End: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ by Sarah Harasym in Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory

- 1988- ‘A Literary Representation of the Subaltern’ in Subaltern Studies

- 1988- “‘A Response to ‘The Difference Within: Feminism and Critical Theory’” in The Difference Within: Feminism and Critical Theory

- 1989- ‘The New Historicism: Political Commitment and the Postmodern Critic’ in The New Historicism.

- 1989- ‘Negotiating the Structures of Violence: A Conversation with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ in Polygraph

- 1989- ‘The Political Economy of Women as Seen by a Literary Critic’ in Coming to Terms: Feminism, Theory, Politics.

- 1989- ‘Who Claims Alterity?’ in Remaking History edited by Barbara Kruger and Phil Mariani

- 1989- ‘Naming Gayatri Spivak’ an interview in Stanford Humanities Review

- 1989- ‘Feminism and Deconstruction, Again’ in Between Feminism and Psychoanalysis by Teresa Brennan

- 1989- ‘Who Needs the Great Works? A Debate on the Canon, Core Curricula, and Culture’ in Harper’s

- 1989- ‘In Praise of Sammy and Rosie Get Laid’ in Critical Quarterly

- 1989- ‘Questions of Multiculturalism’ in Women’s Writing in Exile by Angela Ingram

- 1989- ‘Reading The Satanic Verses’ in Public Culture

- 1989- ‘In A Word. Interview’ with Ellen Rooney in Differences

- 1990- ‘Constitutions and Culture Studies’ in Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities

- 1989- ‘Colloquium on Narrative’ an interview in Typereader

- 1989- ‘Poststructuralism, Marginality, Postcoloniality and Value’ in Literary Theory Today by Peter Collier and Helga Geyer-Rayan.

- 1990- ‘Rhetoric and Cultural Explanation: A Discussion’ in Journal of Advanced Composition

- 1990- ‘Versions of the Margin: J.M. Coetzee’s Foe Reading Defoe’s Crusoe/Roxana’ in Consequences of Theory: Selected Papers of the English Institute 1987-88

- 1990- ‘An Interview with Gayatri Spivak’ in Women in Performance

- 1989-90- ‘Woman in Difference: Mahasweta Devi’s Douloti the Bountiful’ in Cultural Critique

- 1990- ‘The Making of Americans, the Teaching of English, and the Future of Culture Studies’

- 1990- ‘Inscriptions: Of Truth to Size’ in Inscription

- 1991- ‘Reflections on Cultural Studies in the Post-Colonial Conjuncture’ in Critical Studies

- 1991- ‘Time and Timing: Law and History’ in Chronotypes: The Construction of Time by John Bender and David Wellbery

- 1991- ‘Remembering the Limits: Difference, Identity and Practice’ in Socialism and the Limits of Liberalism.

- 1991- ‘Neocolonialism and the Secret Agent of Knowledge: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ in Oxford Literary Review.

- 1991- ‘Identity and Alterity: An Interview’ in Arena

- 1991- ‘Not Virgin Enough to Say That [S]he Occupies the Place of the Other’ in Cardozo Law Review

- 1991- ‘Once Again a Leap into the Postcolonial Banal’ in Differences

- 1991- ‘Extreme Eurocentrism’ in the Abject, America issue of Lusitania

- 1992- ‘The Burden of English’ in The Lie of the Land: English Literary Studies in India

- 1992- ‘French Feminism Revisited: Ethics and Politics’ in Feminists Theorize the Political by Joan Scott and Judith Butler

- ‘1992- ‘Teaching for the Times’ in MMLA (The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association)

- 1992- ‘Asked to Talk About Myself…’ in the Third Text

- 1992- ‘Acting Bits/Identity Talk’ in Critical Inquiry

- 1992- ‘More on Power/Knowledge’ in Rethinking Power by Thomas E. Wartenberg

- 1992- ‘The Politics of Translation’ in Destabilizing Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates

- 1993- ‘Echo’ in New Literary History: A Journal of Theory & Interpretation

- 1993- ‘Excelsior Hotel Coffee Shop’ in Assemblage

- 1993- ‘Foundations and Cultural Studies’ in Questioning Foundations: Truth/Subjectivity/Culture

- 1993- ‘An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spvak’ with Sara Danius and Stefan Jonsson in Boundary

- 1993- ‘Questions of Multiculturalism’ in The Cultural Studies Reader

- 1993- ‘Race Before Racism and the Disappearance of the American: Jack D. Forbes’ Black Africans and Americans: Color, Race and Caste in the Evolution of Red Black Peoples’ in Plantation Society

- 1993- ‘Situations of Value: Feminism and Cultural Work in a Postcolonial Neocolonial Conjuncture’ in Australian Feminist Studies

- 1994- ‘Psychoanalysis in Left Field; and Field-Working: Examples to Fit the Title’ in Speculations After Freud: Psychoanalysis, Philosophy and Culture

- 1994- ‘Introduction’ in Harriet Fraad’s Bringing It All Back Home: Class, Gender, and Power in the Modern Household

- 1994- ‘Bonding in Difference’ in An Other Tongue by Alfred Arteaga

- 1994- ‘Tribal Woes’ in Economic Times

- 1994- ‘Response to Jean-Luc Nancy’ in Thinking Bodies by Juliet Flower, MacCannell and Laura Zakarin

- 1994- ‘In the New World Order: A Speech’ in Marxism in the Postmodern Age: Confronting the New World Order

- 1994- “ ‘What Is It For?’: Functions of the Postcolonial Critic” in Nineteenth-Century Contexts

- 1994- ‘Responsibility’ in Boundary

- 1995- ‘Supplementing Marxism’ in Whither Marxism by Steven Cullenberg and Bernd Magnus

- 1995- ‘Empowering Women?’ in Environment

- 1995- ‘At the Planchette of Deconstruction Is/In America’ in Deconstruction is/in America: A New Sense of the Political

- 1995- ‘A Dialogue on Democracy’ in Socialist Review

- 1995- ‘Ghostwriting’ in Diacritics

- 1995- “ ‘Woman’ as Theater: Beijing 1995’” in Radical Philosophy

- 1995- ‘Love, Cruelty, and Cultural Talks in the Hot Peace’ in Parallax

- 1995- ‘Running Interference’ an interview with Julie Stephens in Australian Women’s Book Review

- 1996- ‘Lives’ in the Confessions of the Critics by H. Aram Veeser

- 1996- ‘Further Notes on Imperialism Today’ in Against the Current

- 1996- ‘Diasporas Old and New: Women in a Transnational World’ in Textual Practices

- 1996- ‘Setting to Work’ in A Critical Sense: Interviews with Intellectuals by Peter Osborne

- 1996- ‘Scattered Speculations on the Question of Linguistic Culture’ in Proceedings of the International Symposium on “Linguisticulture: Where Do We Go From Here?” by Takayuki Yokota-Murakami

- 1997- ‘At Home with Others’ at Rovaniemi Art Museum

- 1997- ‘City, Country, Agency’ in Theatres of Decolonization: [Architecture] Agency [Urbanism] by Vikramaditya Prakash

- 1997- ‘Of Poetics and Politics’ in Politics-Poetics: documenta

- 1997- ‘Abinirman-Anubad’ in Paschimbanga Bangla Akademi Patrika

- 1997- ‘Attention: Postcolonialism!’ in Journal of Caribbean Studies

- 1998- ‘Foucault and Najibullah’ in Lyrical Symbols and Narrative Transformations: Essays in Honor of Ralph Freedman

- 1998- ‘Lost Our Language- Underneath the Linguistic Map’ in Imported: A Reader Seminar by Rainer Ganahl.

- 1998- ‘Derrida and Deconstruction’ in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics

- 1998- ‘Feminist Literary Criticism’ in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Edward Craig

- 1998- ‘Gender and International Studies’ in Millennium: Journal of International Studies

- 1998- ‘Three Women’s Texts and Circumfession’ in Postcolonialism and Autobiography by Alfred Hornung and Ernstpeter Ruhe.

- 1999- ‘Moving Devi’ in Devi: The Great Goddess by Vidya Dehejia

- 1999- ‘American Gender Studies Today’ in Women: A Cultural Review

- 1999- ‘Translation as Culture’ in Translating Cultures by Isabel Carrera Suárez

- 1999- ‘Report by the Denotified Nomadic Tribal Right Action Group: An Interview’ in Interventions

- 2000- ‘Dialogue: The Future of Feminism’ in Feminist Review

- 2000- ‘Schmitt and Post-Structuralism: A Response’ in Cardozo Law Review

- 2000- ‘Foreword: Upon Reading the Companion to Postcolonial Studies’ to A Companion to Postcolonial Studies by Henry Schwarz and Sangeeta Ray

- 2000- ‘From Haverstock Hill Flat to US Classroom, What’s Left of Theory? In What’s Left of Theory by Judith Butler

- 2000- “Thinking Cultural Questions in ‘Pure’ Literary Terms” in Without Guarantees: In Horror of Stuart Hall by Paul Gilroy

- 2000- ‘The New Subaltern: A Silent Interview’ in Mapping Subaltern Studies and the Postcolonial by Vinayak Chaturvedi

- 2000- ‘Deconstruction and Cultural Studies: Arguments for a Deconstructive Cultural Studies’ in Deconstructions by Nicholas Royle

- 2000- ‘Megacity’ in Grey Room

- 2000- ‘Claiming Transformations: Travel Notes with Pictures’ in Transformations: Thinking through Feminism by Sara Ahmed

- 2000- ‘Other Things Are Never Equal’ - a speech by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in Rethinking Marxism

- 2000- ‘Chotti Munda Ebong Tar Teer/Chotti Munda and his Arrow’ in Connect

- 2000- ‘Discussion: Afterword on the New Subaltern’ in Subaltern Studies XI: Community, Gender and Violence by Partha Chatterjee and Pradeep Jeganathan

- 2001- ‘A Moral Dilemma’ in What Happens to History: the Renewal of Ethics in Contemporary Thought by Howard Marchitello

- 2001- ‘Questioned en Translation: Adrift’ in Public Culture

- 2001- ‘A Note on the New International’ in Parallax

- 2001- ‘Righting Wrongs’ in Human Rights, Human Wrongs by Nicholas Owen

- 2002- ‘Resident Alien’ in Relocating Postcolonialism by David Theo Goldberg and Ato Quayson2002- ‘The Occidental Accident’ an interview with Deepak Narang Sawhney in Unmasking L.A.: Third Worlds and the City

- 2002- ‘Postcolonial Scholarship- Productions and Directions: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ in Communication Theory

- 2002- ‘Gender and International Studies’ in Gendering the International by Louiza Odysseos and Hakan Seckinelgin

- 2002- ‘The Rest of the World: A conversation with Gayatri Spivak’ in Hope: New Philosophies for Change by Mary Zournazi

- 2003- ‘A Conversation with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Politics and the Imagination’ in Signs

- 2003- ‘Empire, Union, Center, Satellite: The Place of Post-Colonial Theory in Slavic/Central and Eastern European/(Post-)Soviet Studies, a questionnaire’ in Ulbandus: The Salvic Review of Columbia University

- 2003- ‘The Politics of the Production of Knowledge’ an interview with Stuart J.Murray in Just Being Difficult? Academic Writing in the Public Arena

- 2003- ‘In Memoriam: Edward W. Said’ in the Preface to the Serbian translation of A Critique of Postcolonial Reason

- 2004- ‘Questionnaire on India Today’ in Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences

- 2004- ‘Terror: A Speech After 9/11’ in Boundary

- 2004- ‘Globalicities: Terror and its Consequences’ in CR: The New Centennial Review

- 2004- “‘On the Cusp of the Personal and the Impersonal’: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak” in Biography

- 2004- ‘What is Enlightenment?’ in Polemic: Critical or Uncritical by Jane Gallop

- 2004- ‘At Both Ends of the Spectrum’ in Light Onwords/ Light Onwards

- 2004- ‘Not Really A Properly Intellectual Response: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ in Positions

- 2004- ‘Harlem’ in Citizens Without Cities by Aaron Levy

- 2004- ‘Ethics and Politics in Tagore, Coetzee, and Certain Scenes of Teaching’ in Diacritics

- 2005- ‘Postcolonial Theory and Literature’ in New Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- 2005- ‘Resistance That Cannot Be Recognized as Such: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’ in N.Paradoxa

- 2005- ‘Remembering Derrida’ in Radical Philosophy

- 2005- ‘Thinking About Edward Said: Pages from a Memoir’ in Critical Inquiry

- 2005- ‘Class Individual: Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak on Jacques Derrida’ in Artforum

- 2005- ‘Forum: The Legacy of Jacques Derrida’ in PMLA (Publications of the Modern Language Association)2005- ‘Guest Column: Roundtable on the Future of the Humanities in a Fragmented World’ in PMLA

- 2005- ‘Touched by Deconstruction’ in Grey Room

- 2005- ‘Translating into English’ in Nation, Language and the Ethics of Translation by Sandra Bermann and Michael Wood

- 2005- “‘The Slightness of My Endeavor’: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak” in Comparative Literature by Eric Hayot

- 2005- ‘Scattered Speculations on the Subaltern and the Popular’ in Postcolonial Studies

- 2005- ‘Commonwealth Literature and Comparative Literature’ in Re-imagining Language and Literature for the 21st Century by Suthira Duangsamorn

- 2005- ‘Politics, Language, Art’ in “Please Teach Me…” Rainer Ganahl and the Politics of Learning by William Kaizen

- 2005- ‘Learning from De Man: Looking Back’ in Boundary

- 2005- ‘IKS and Globalization’ in Indilinga

- 2005- ‘Notes toward a Tribute to Jacques Derrida’ in Differences

- 2005- ‘Made for a Hybrid Viewer: Tramjatra’ in Tramjatra: Imagining Melbourne and Kolkata by Tramways

- 2006- ‘World Systems and the Creole’ in Narrative

- 2006- ‘Culture Alive’ in Theory, Culture & Society

- 2006- ‘Close Reading’ in PMLA (Publishings of the Modern Language Association)

- 2006- ‘The Politics of Mourning’ in Rrrevolutionnaire: Conversations in Theory by Gregg Lambert and Aaron Levy

- 2007- ‘Religion, Nationalism and Politics: A Conversation with Achille Mbembe’ in Boundary

- 2007- ‘Nationalism and the Imagination’ in Nation in Imagination: Essays on Nationalism, Sub-Nationalisms and Narration

- 2007- ‘Western Marxism and the Legacy of New Social Movements’ in Frontier

- 2008- ‘A response to Frigga Haug’s Call for Left feminist Projects’ in Frontier

- 2009- “‘The Modern Prince…’to come’?” in Journal of Visual Culture

- 2009- ‘Rethinking Comparativism’ in New Literary History